Authors: Charlotte Baker DrPH MPH CPH ⊕Truveta, Inc, Bellevue, WA, Brianna M. Goodwin Cartwright ⊕Truveta, Inc, Bellevue, WA, Patricia J. Rodriguez, PhD MPH ⊕Truveta, Inc, Bellevue, WA, Samuel Gratzl PhD ⊕Truveta, Inc, Bellevue, WA, Nicholas Stucky, MD PhD ⊕Truveta, Inc, Bellevue, WA

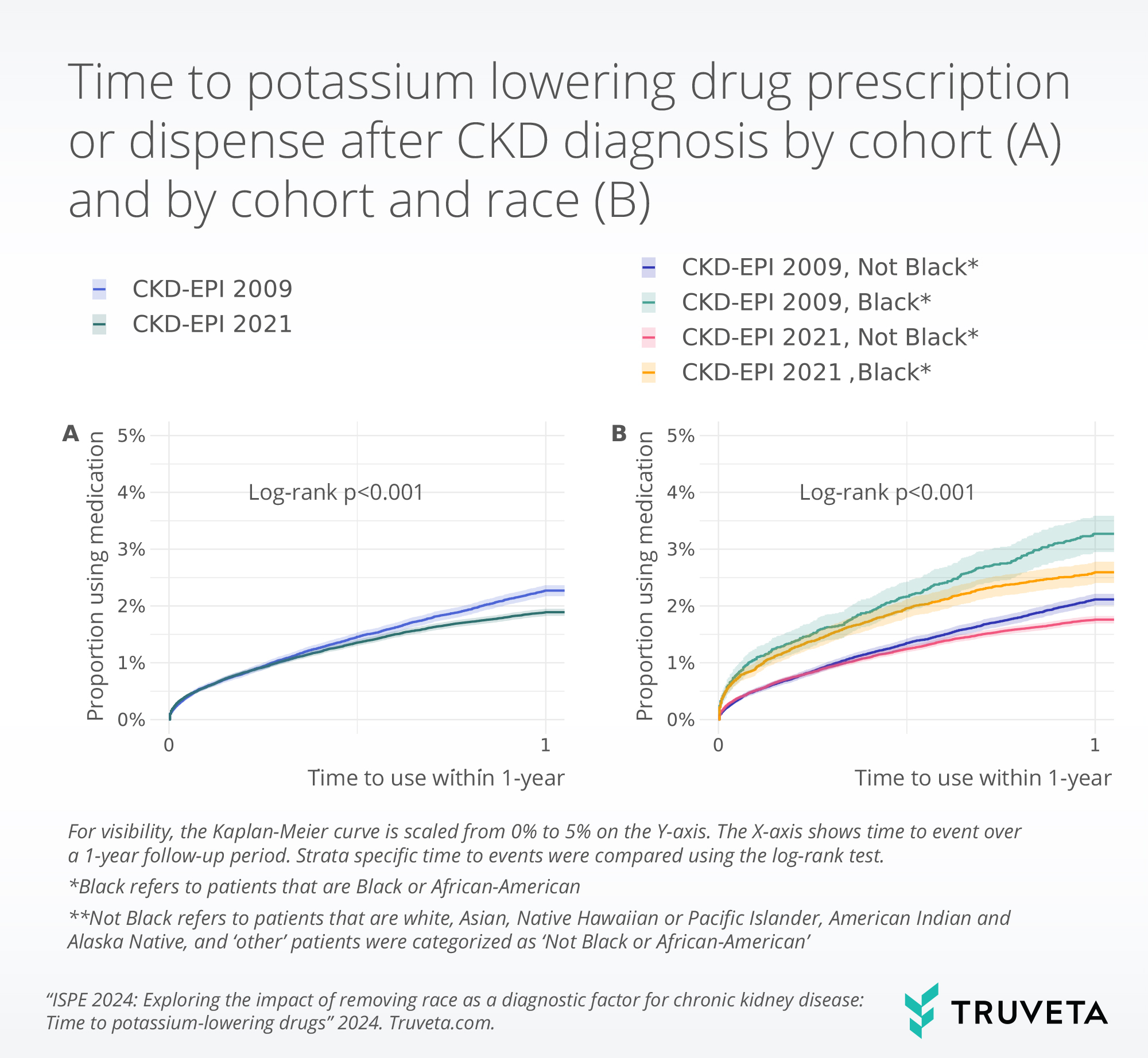

- Prescription and dispense of potassium binders within the first year of CKD diagnosis decreased significantly after the implementation of the race-free CKD-EPI creatinine equation when compared with the race-inclusive CKD-EPI creatinine equation.

- We found that use of potassium binders decreased significantly after race was removed from the CKD-EPI creatinine eGFR equation.

- Differences in use existed within Black patients and within non-Black patients in both cohorts but there was no significant difference between Black and non-Black patients

- Fifty-four percent of the present study’s patient population developed hyperkalemia, but only 2% of patients obtained a prescription for these potassium-lowering drugs.

This blog is an extension of our poster presented at the Annual Conference for the International Society of Pharmacoepidemiology, titled Decreased Hazard of Potassium Lowering Drug Prescription & Receipt Following Implementation of the 2021 CKD-EPI Creatinine GFR Equation.

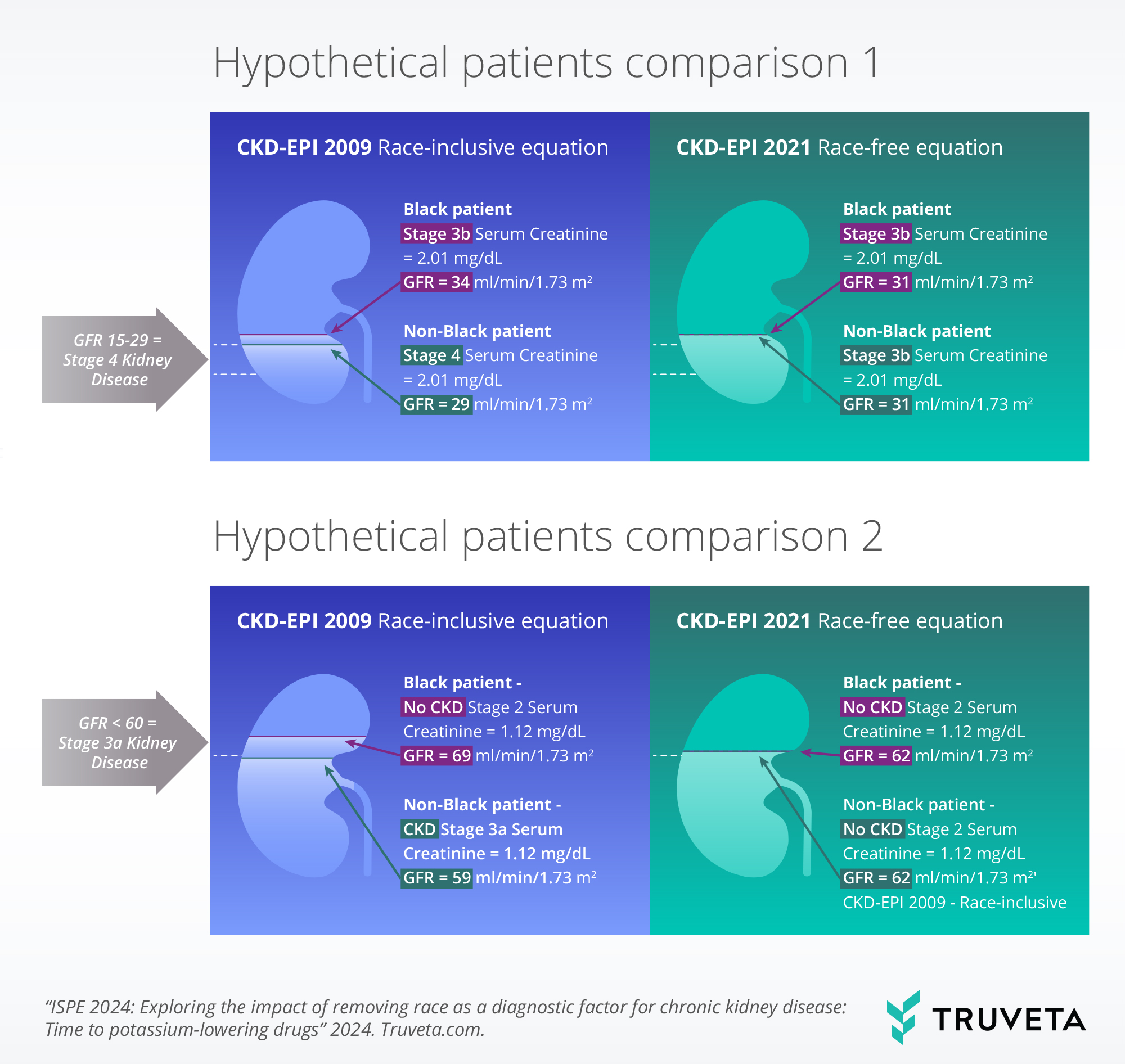

When treating patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), the social construct of race, especially in the US, affects both the occurrence of disease and the treatment of disease. Black patients constitute 18.6% of all patients with CKD in the US, and Black patients are more likely than white patients to have poor disease outcomes (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2023; National Kidney Foundation, 2024; Kizer, 2022; Reese, 2021; Ashby, 2011). Recently, the National Kidney Foundation-American Society of Nephrology (NKF-ASN) Task Force and KDIGO recommended that the 2021 CKD-EPI Creatinine Equation – the global equation used to diagnose and stage patients with CKD – remove race from the calculation of the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), which measures how well the kidneys are filtering (Delgado, 2021; KDIGO, 2024). The removal of race improved the time to CKD diagnosis for all patients, especially Black patients (Baker, 2023).

Patients with CKD are at elevated risk for hyperkalemia, a condition in which potassium levels are too high (serum potassium level ≥ 5.0 mmol/L). Hyperkalemia increases the risk of arrythmias and cardiac arrest, hospitalization, visits to the emergency department, and mortality (DeNicola, 2024; Montford, 2017). Medications used to treat patients with CKD, who also have other comorbidities like type 2 diabetes or hypertension, can increase the risk of hyperkalemia and poor cardiovascular outcomes. Managing hyperkalemia usually includes potassium-lowering drugs, such as potassium blockers, sodium bicarbonate, and diuretics. With newer potassium blockers available (e.g., patiromir, sodium zirconium cyclosilicate, sodium polystyrene sulfonate, and calcium polystyrene sulfonate), patients can remain on renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system inhibitors (RAASi) to manage both CKD and the cardiovascular or diabetes-related comorbid conditions (DeNicola, 2024).

Truveta Research sought to explore the changes in time to prescription of potassium-lowering drugs before and after the implementation of the race-free CKD-EPI 2021 creatinine equation to see the impact the change in the equation might have had on these prescriptions. The removal also resulted in identifying CKD when the kidneys were functioning better for Black patients (Baker, 2023).

You can also view this study directly in Truveta Studio.

Methods

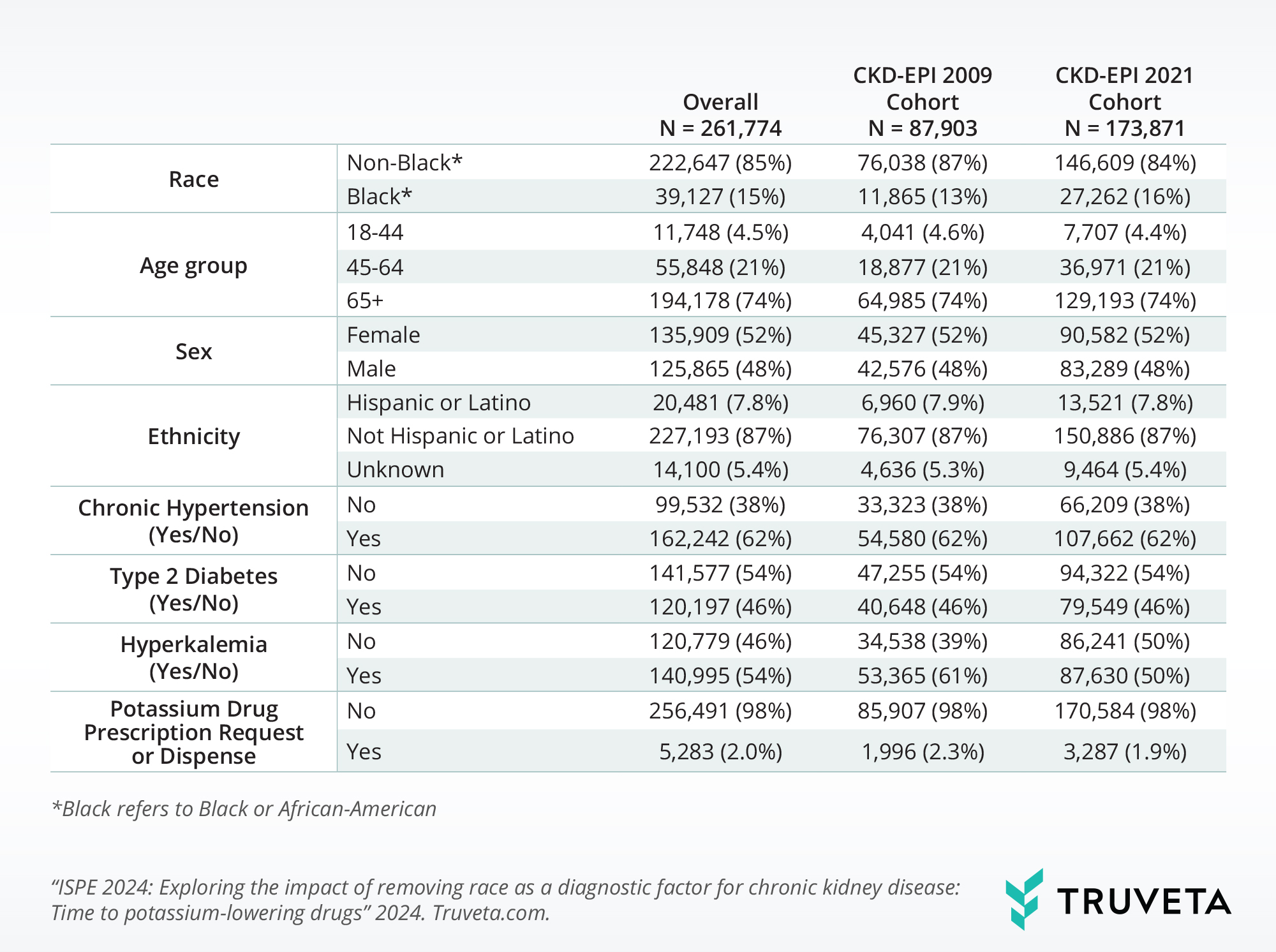

Patients were excluded if they had a missing or unknown race or sex. We also excluded patients if they had a diagnosis of renal failure, polycystic kidney disease, or acute kidney injury (AKI) at or before CKD diagnosis. AKI patients were excluded because of an inability to discern in the data whether 1) AKI occurred because of CKD or whether CKD occurred because of AKI and because 2) patients with AKI could be sicker than other patients that develop CKD.

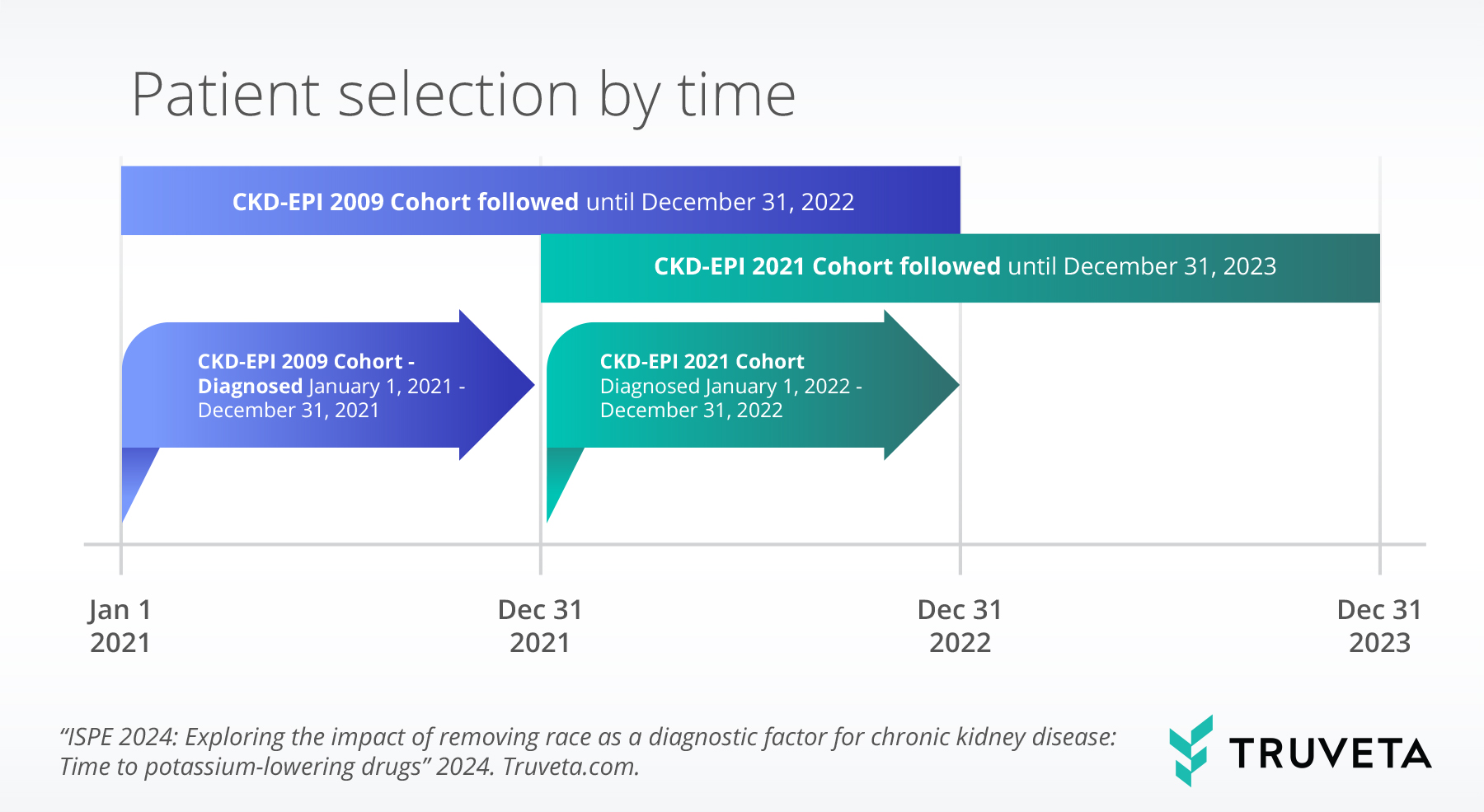

To compare prescription and dispense before and after recommending the removal of race from diagnosing CKD, we used December 31, 2021 as a proxy for the end of the use of the race-inclusive CKD-EPI 2009 equation.

We then used Kaplan-Meier curves stratified by cohort and the interaction of cohort and race to describe probability of outcome, as well as Cox proportional hazard models to compare time to first prescription or dispense. We then adjusted for sex, age, race, ethnicity, income, education, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, obesity, hyperlipidemia, and renal failure.

We identified all conditions using ICD-9-CM, ICD-10-CM, and SNOMED CT codes. We identified all medications using RxNorm codes.

Results

Fifty-four percent of the present study’s patient population developed hyperkalemia, but only 0.1% of patients obtained a prescription for these potassium-lowering drugs.

When we took into account other factors that contribute to medication prescription and dispense, including SDOH, other medical conditions, and age, we found there was no statistically significant difference by race (Black patients AHR 0.79, non-Black patients AHR 0.90, p=0.1) in patients receiving potassium-lowering drugs. However, Black patients’ use appeared to be reduced by 21% whereas their non-Black counterparts’ use was reduced only by 10% after the removal of race from the recommended eGFR equation.

Discussion

Following the removal of race from the CKD-EPI creatinine eGFR equation, we found that patients received potassium-lowering drugs at lower rates. The higher probability of prescription observed for Black patients could be due to earlier diagnosis, lower staging of disease at diagnosis, and earlier access to treatment since race was removed from the CKD-EPI creatinine equation (Baker, 2023). Future research is needed to identify whether this change persists over time.

SDOH and disease comorbidities are important for the development of CKD and disease progression (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2023; Baker, 2023; Kim, 2017; Norton, 2016). These factors were significant contributors to potassium-lowering drug prescription and serum creatinine doubling within a year of CKD diagnosis. This may be due to a lack of consistent medical care due to frequent moves, poor access to care or medications, structural barriers leading to late diagnosis, or biased diagnostic guidelines like CKD-EPI 2009.

As with all research, there are some limitations in this study. We limited the time to potassium-lowering medications to one year following diagnosis in this analysis because the change in the CKD-EPI creatinine eGFR equation was so recent. The longer CKD-EPI 2021 is used, the more data will be available to observe time-based changes in treatment and diagnosis. Future research could explore the ongoing impact of removing race from the CKD-EPI creatinine equation. Other future analyses could explore new questions, such as how the removal of race has impacted how CKD is being managed, as well as the effectiveness of newer potassium-lowering drugs in treating CKD over time.

These findings are consistent with data access on February 6, 2024.

You can also view this study directly in Truveta Studio.

Citations

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). Chronic Kidney Disease in the United States, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/kidney-disease/php/data-research/

National Kidney Foundation. Health Disparities | National Kidney Foundation. https://www.kidney.org/advocacy/legislative-priorities/health-disparities

Committee on A Fairer and More Equitable, Cost-Effective, and Transparent System of Donor Organ Procurement, Allocation, and Distribution. Realizing the Promise of Equity in the Organ Transplantation System. Kizer KW, English RA, Hackmann M, editors. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2022. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/26364

Reese PP, Mohan S, King KL, Williams WW, Potluri VS, Harhay MN, et al. (2021). Racial disparities in preemptive waitlisting and deceased donor kidney transplantation: Ethics and solutions. American Journal of Transplantation, 21(3):958–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajt.16392

Ashby VB, Port FK, Wolfe RA, Wynn JJ, Williams WW, Roberts JP, et al. Transplanting Kidneys Without Points for HLA-B Matching: Consequences of the Policy Change. American Journal of Transplantation. 2011;11(8):1712–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03606.x

Delgado C, Baweja M, Crews DC, et al. (2021). A Unifying Approach for GFR Estimation: Recommendations of the NKF-ASN Task Force on Reassessing the Inclusion of Race in Diagnosing Kidney Disease. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 32(12), 2994. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2021070988

KDIGO. (2013). Chapter 1: Evaluation of CKD, KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney International Supplements, 105(4S), 19–62. https://doi.org/10.1038/kisup.2012.64

Baker C, Gratzl S, Rodriguez PJ, et al. (2024). Effects of changes in calculating GFR using KDIGO standards: Discordance in the Staging and Timing of Diagnosis of Chronic Kidney Disease. medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.12.21.23300415

De Nicola L, Ferraro PM, Montagnani A et al. (2024). Recommendations for the management of hyperkalemia in patients receiving renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors. Intern Emerg Med 19, 295–306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-023-03427-0

Montford JR, & Linas S (2017). How Dangerous Is Hyperkalemia? Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 28(11). https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2016121344

Kim T, Rhee CM, Streja E, et al. (2017). Racial and Ethnic Differences in Mortality Associated with Serum Potassium in a Large Hemodialysis Cohort. Am J Nephrol, 45(6):509-521. https://doi.org/10.1159/000475997

Norton JM, Moxey-Mims MM, Eggers PW, et al. (2016). Social Determinants of Racial Disparities in CKD. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 27(9), 2576–2595. https://doi.org/10.1681/asn.2016010027