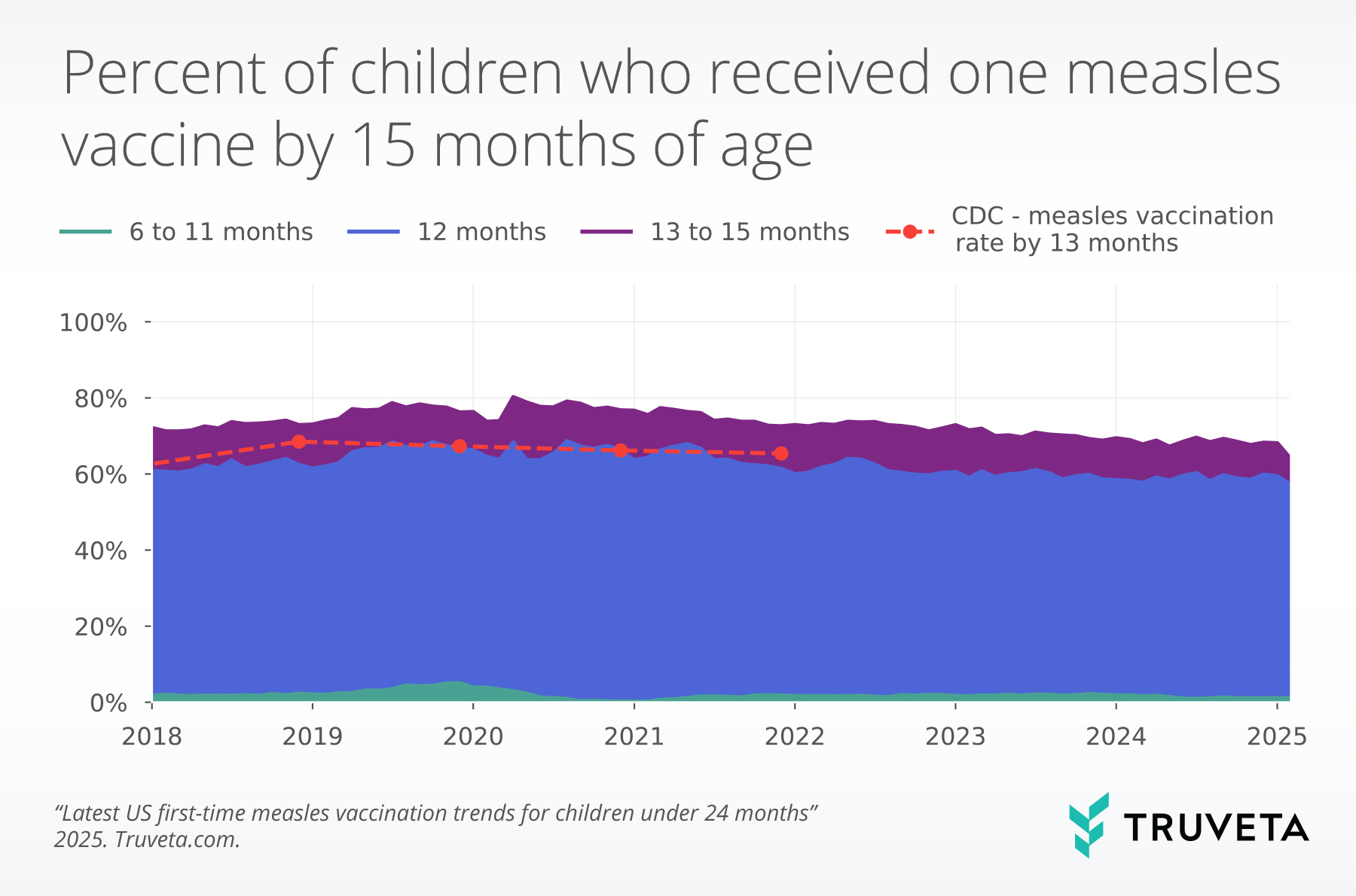

- Measles vaccination rates for children under 24 months in 2024 remain lower than in 2020.

- In 2024, the average yearly measles vaccination rate for children by 13 months was 58.9% and 68.5% for children by 15 months.

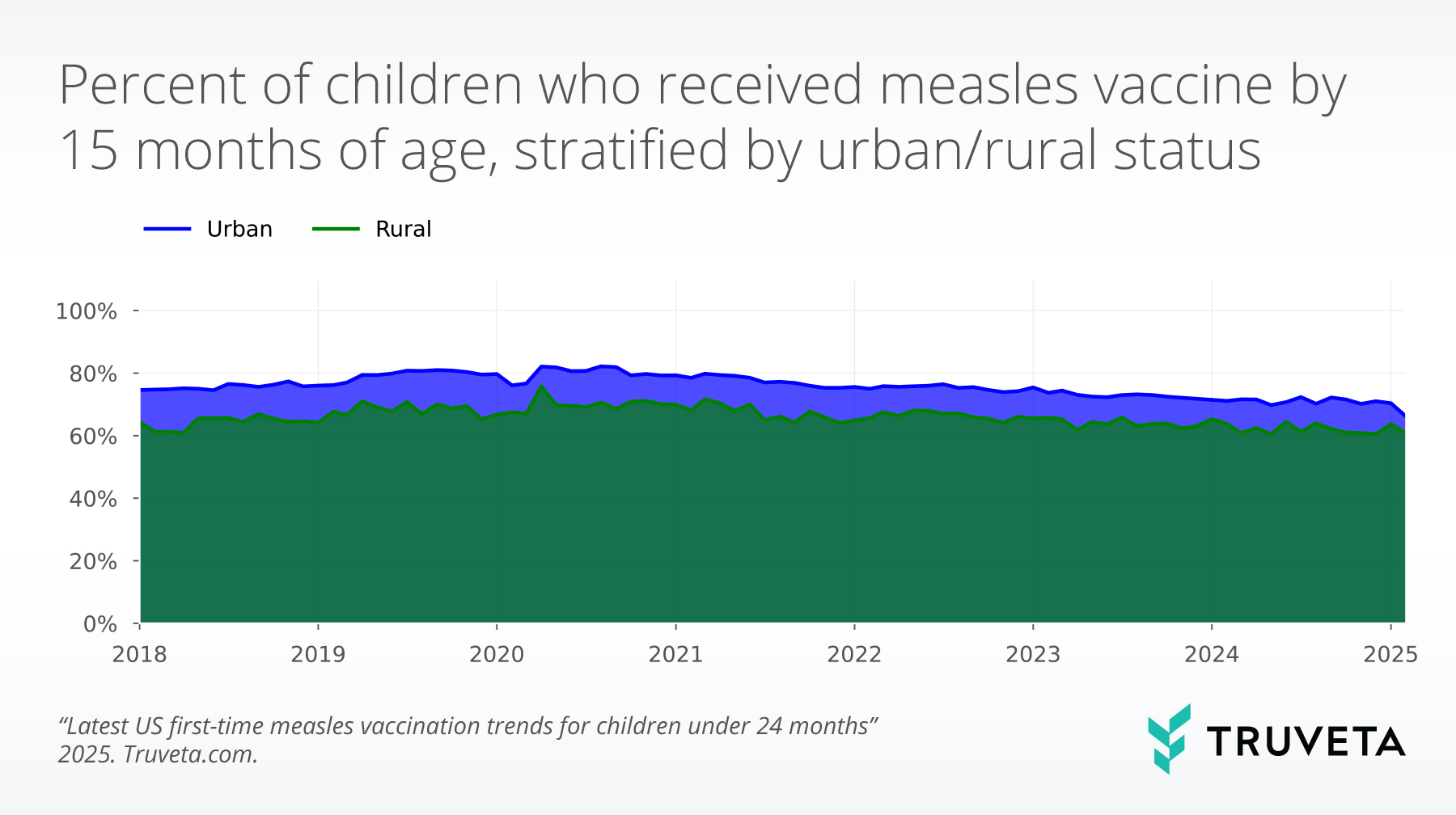

- Vaccination patterns for children living in both rural and urban locations followed similar trends; however, across the study period on average 75.0% of children in urban areas received one measles dose by 15 months compared to 65.5% of children in rural areas.

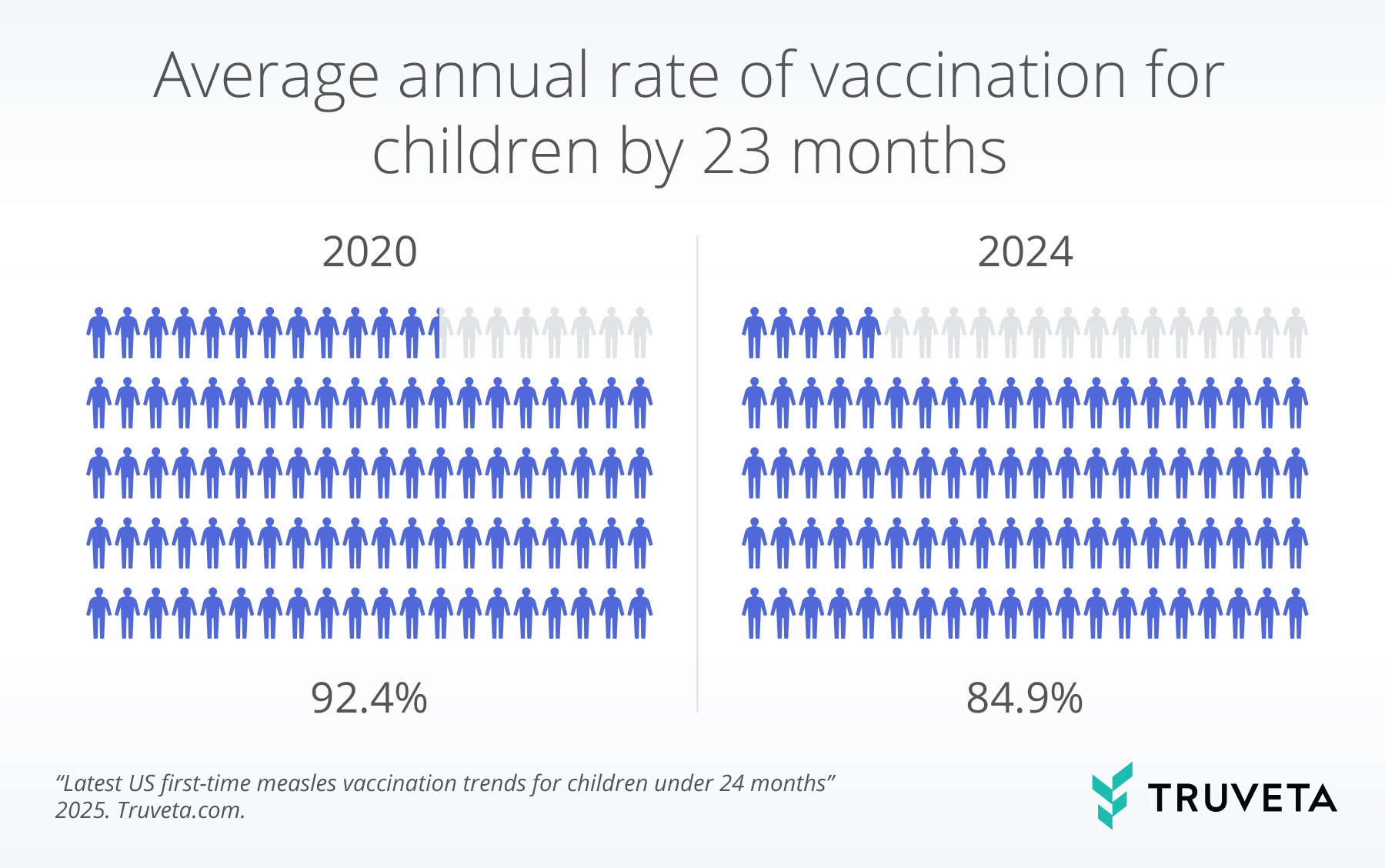

- The average annual rate of vaccination for children by 23 months increased from 90.2% in 2018 to 92.4% in 2020, before decreasing to 84.9% in 2024. This means for every 100 children, almost eight fewer children received one measles dose in 2024 compared to 2020.

Measles is among the most contagious human diseases and can lead to pneumonia, encephalitis, hospitalization, and death (1, 2). Before the vaccine became available, nearly every child contracted it within their first 15 years of life (3). Between one to three in every 1,000 children who get measles will die from associated complications (2).

As of March 27, 2025, the CDC has reported 483 measles cases in 2025, well surpassing the 285 total cases in 2024 (4). The measles vaccine (given in the United States as one of two combination vaccines: measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) or measles-mumps-rubella-varicella (MMRV)) is the best way to protect against the disease (5); one dose is 93% effective, and two doses are 97% effective (5). The first measles vaccine was licensed in 1963; by 1981, the number of reported measles cases in the US had begun to substantially decline (3, 6). Due to the highly effective vaccine, in 2000, measles was declared eliminated from the US, meaning community transmission had stopped. This elimination status has been maintained for the past 25 years (3). From 1994 to 2023, it is estimated that measles vaccinations averted an estimated 105 million cases of measles, 13 million hospitalizations, and 85,000 deaths in the US (7).

The first dose of the measles vaccine is recommended between 12 to 15 months of age, with a second dose between 4 to 6 years of age. The CDC reports immunization coverage for children under 35 months (NIS-Child survey data) (8) and at kindergarten entry (approximately 5 to 6 years of age) (9). The NIS-Child survey data is comprehensive; however, the most recent data is from children born in 2021.

We explore month-level first-time measles (MMR or MMRV) vaccination rates and compare our results (through February 2025) to rates reported by the CDC in the most recent NIS-Child survey data. You can also view this study — including definitions and code — directly in Truveta Studio.

Methods

Using a subset of Truveta Data, we included a population of children who had an outpatient visit between the ages of 12 to 15 months (365 – 450 days) between January 2018 through February 2025. Children were also required to have at least one outpatient visit in their first year of life.

First-time vaccination on schedule (prior to 15 months)

We identified children who received a measles vaccine (MMR or MMRV) and the age at which they received their first vaccine. Vaccination events recorded prior to age 6 months (182 days) were assumed to be erroneous and excluded (10).

We identified children who received a vaccine between 6 and 15 months (timing aligned with routine and outbreak/travel guidelines from the CDC). We plot the unadjusted monthly rates of vaccines administered per children with an outpatient encounter between 12 to 15 months. Children were only counted in one month. If they had multiple encounters between 12 to 15 months, the last was selected. All children who received the vaccine were plotted in the month of their 12 to 15-month visit, regardless of when they received the vaccine. We also plot data from CDC’s NIS-Child survey, which presents an annual rate of children who received one dose of the measles vaccine by 13 months (the last survey year represents children born in 2021). The CDC data are based on children’s birth year; therefore, the data were shifted one year forward to align with the data in this study.

We stratified the data by rural versus urban residency using the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy Data Files (11). A threshold of 0.3 was used in this study to differentiate between rural and urban status. We calculated the unadjusted rate of children who received a vaccination by 15 months of age. We plot and describe the differences in vaccination status by residency.

Late first-time vaccine dose (prior to 24 months)

For subsequent analyses we required our initial population to also have an outpatient visit between 16 to 23 months of age prior to May 2024. For this population, we describe the children who received a measles vaccine late but prior to 24 months. We describe the overall rate of vaccination and compare to the CDC NIS-Child rates for children by 19 months.

Similar to the prior analysis, children were only counted once, and they were counted at the time of their 12 to 15 month visit. If a child had multiple visits in this range, they were counted at the last visit. The figure was truncated to only include data for children in the cohort that would have sufficient time to have a follow up.

For children who received a measles vaccine, we describe the distribution of ages at which children received their first vaccine each year.

Results

We included 685,604 children in the study.

First-time vaccination on schedule (prior to 15 months)

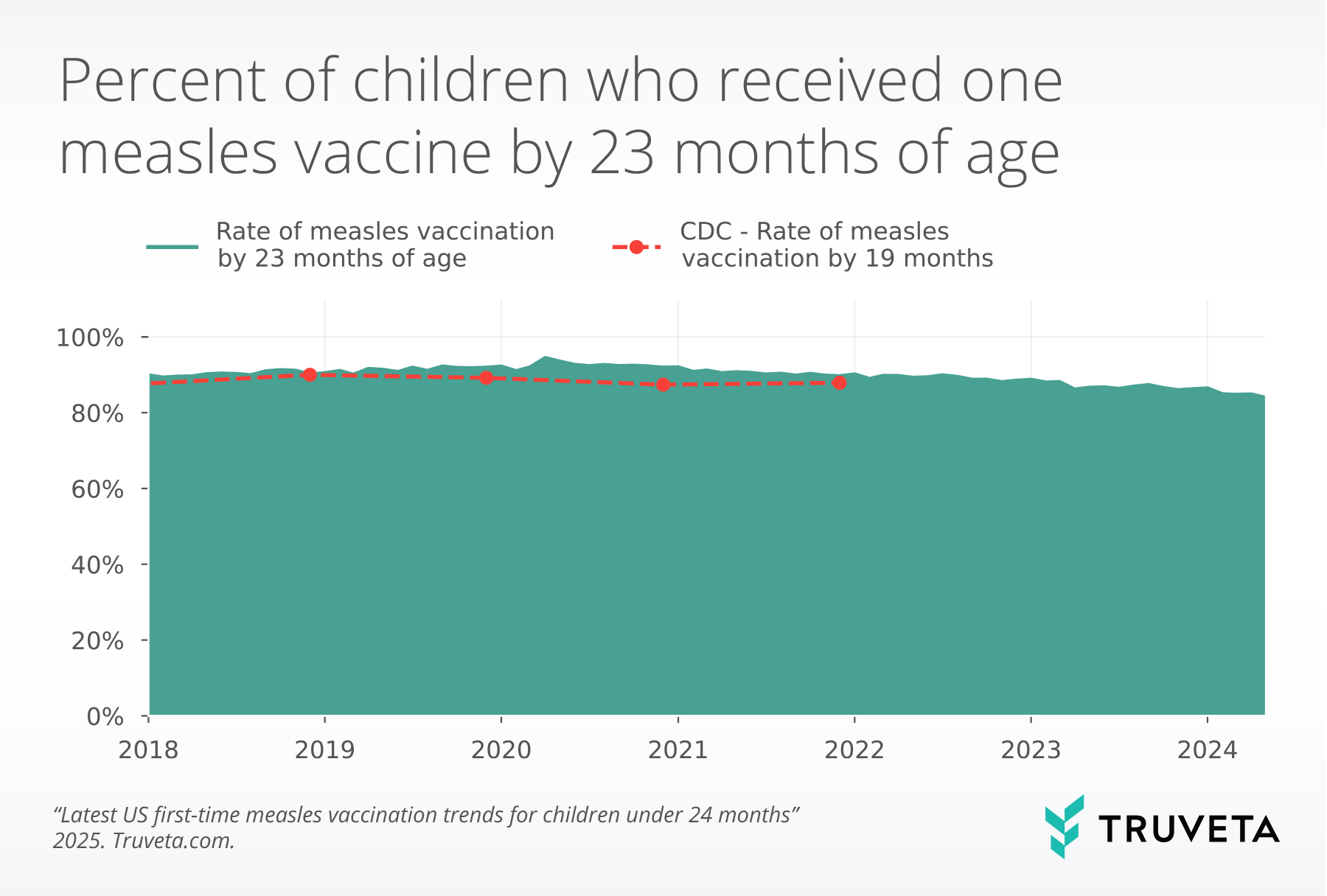

In 2024, the average yearly vaccination rate for children at 13 months was 58.9%. The rate of vaccination by 13 months increased from 61.9% in 2018 to 65.9% in 2020 before decreasing to 58.9% in 2024. The yearly unadjusted rates we observed are similar to the CDC NIS-Child results by 13 months (children born in 2021).

We also observe an additional 10.4% of children receive a first-time measles vaccine between 13 to 15 months across all years studied.

Within these data, by 15 months, 68.5% of children in 2024 received at least one measles vaccine dose, which is still within the CDC recommended window. This rate has decreased almost 10 percentage points since the 2020 rate of 77.2%.

These data complement the CDC reports and suggest that although most children receive a first-time vaccine prior to 13 months, a substantial number receive a first-time vaccine after, but still within the guidelines.

CDC data from NIS-Child are superimposed on this graph, presented for birth years 2017-2021, but shifted forward a year to reflect the 13-month vaccination rate.

Children living in both rural and urban locations followed similar trends; however, across the study period on average 75.0% of children in urban areas received one measles vaccine by 15 months, compared to 65.5% of children in rural areas.

This means for 20 children living in an urban environment, about 15 would have received a first-time vaccine by 15 months, while for 20 children living in a rural environment, only 13 would have received a first-time vaccine prior to 15 months.

Late first-time vaccine dose (prior to 24 months)

561,549 children were included in the subsequent analysis.

The average annual rate of vaccination for children by 23 months increased from 90.2% in 2018 to 92.4% in 2020, before decreasing to 84.9% in 2024.

This means that for every 100 children, almost eight fewer children received a first-time measles vaccine in 2024 compared to 2020. The yearly unadjusted rates we present are similar to CDC NIS-Child results at 19 months (through birth year 2021).

CDC data from NIS-Child are superimposed on this graph, presented for birth years 2017-2021, but shifted forward a year to reflect the 19-month vaccination history.

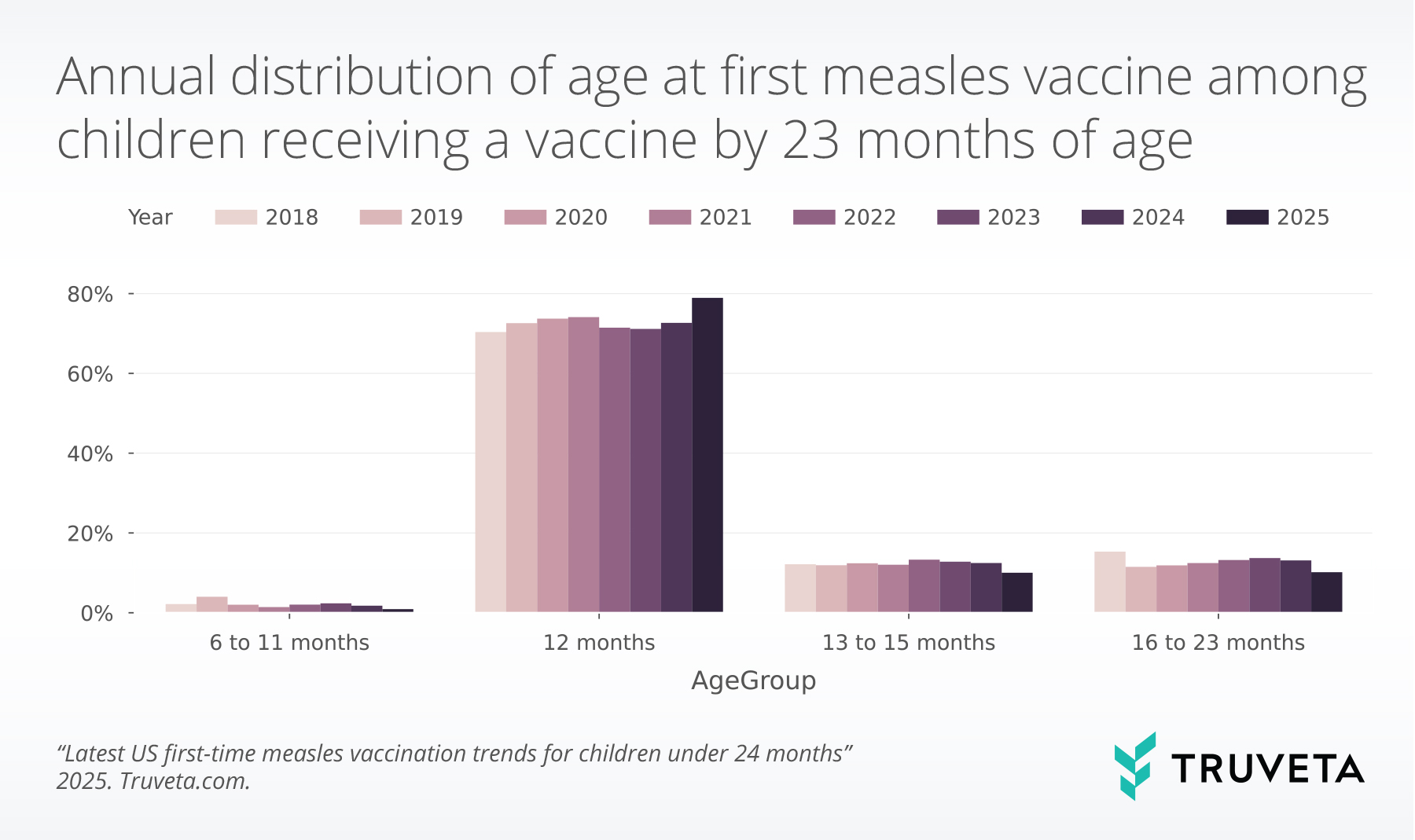

Of the children who received a measles vaccine, a larger proportion in the 6 to 11-month age group received the vaccine in 2019. An early dose of MMR is indicated by the CDC ahead of international travel to areas where measles is endemic or in an active outbreak setting.

From 2019 to 2023, among children who received a measles vaccine, an increasing proportion received the vaccine late (between 16 to 23 months).

However, in 2024 and so far in 2025, we observe a small increase in the percentage of children receiving a vaccine at 12 months.

Across the study period, among children who received a measles vaccine, on average 73.1% received the vaccine at 12 months, 12.1% received it between 13 to 15 months, 12.7% received the vaccine late (16 to 23 months), and 2.1% received the vaccine early (6 to 11 months).

Discussion

The decline in on-time measles vaccination rates after 2020 aligns with broader disruptions to routine immunization services during the COVID-19 pandemic (12). Studies have reported decreased pediatric healthcare visits and delayed vaccinations during this period, raising concerns about increasing susceptibility to vaccine-preventable diseases, including measles (13). The results presented in this study suggest that measles vaccination rates for children at 15 months and 23 months have not returned to pre-pandemic levels, but rather have continued to decrease.

Among this pediatric population, 10% received their first measles vaccine between 13– to 15 months. While the NIS-Child data from CDC data tracks vaccination rates by 13 months, our findings suggest that a substantial number of children receive a measles vaccine within the recommended window in months 13 to 15, likely due to the timing of well-child visits.

The observed increase in the proportion of children aged 6 to 11 months receiving their first measles vaccine in 2019 is consistent with both domestic and international epidemiological trends for measles observed in 2019. In the US, there were over a thousand measles cases in 2019, the highest number of cases nationally since elimination was declared (4). These outbreaks prompted the recommendation for an early (6 to 11 month) measles vaccination dose for children in outbreak-affected areas (14). Globally, 2019 also had the highest number of measles cases in 23 years, likely leading to increased recommendations for an early dose prior to international travel (15).

Our findings also highlight persistent rural-urban disparities in measles vaccination coverage, with children in rural areas less likely to receive their first dose on time. This pattern is consistent with prior research showing lower vaccination coverage in rural populations due to factors such as healthcare access barriers, provider availability, and vaccine hesitancy (16). Addressing these disparities requires targeted public health strategies, including improving healthcare accessibility, increasing provider engagement, and addressing vaccine confidence in underserved communities (17).

This study has several limitations. First, the analysis is based on unadjusted rates and does not account for demographic or socioeconomic factors that may influence vaccination uptake. Second, measles vaccination records rely on electronic health data, which may be incomplete if a child’s vaccination occurred outside of a constituent Truveta healthcare system. These results should be interpreted with these limitations in mind and future research is needed to explore factors influencing vaccination timing and coverage.

To maintain measles elimination in the US, high population-level measles vaccination coverage with two doses of the measles vaccine remains critical. Our findings show that while most children receive their first measles vaccine on time, a growing proportion receive it up to a year late (between 16 and 23 months), and in 2024 15% of children did not receive any measles vaccine before 24 months. We explore the trends in second dose measles vaccine, for children up to 72 months of age, in an additional study.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, rural-urban disparities, and evolving epidemiological trends all contribute to shifts in vaccination timing. Strengthening vaccination outreach, particularly in rural communities, and ensuring timely administration of the first dose remain essential public health priorities.

These are preliminary research findings and not peer reviewed. Data are constantly changing and updating. These findings are consistent with data accessed on March 28, 2025.

Citations

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, About Measles, Measles (Rubeola) (2024). https://www.cdc.gov/measles/about/index.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Measles Symptoms and Complications, Measles (Rubeola) (2024). https://www.cdc.gov/measles/signs-symptoms/index.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, History of Measles, Measles (Rubeola) (2024). https://www.cdc.gov/measles/about/history.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Measles Cases and Outbreaks, Measles (Rubeola) (2025). https://www.cdc.gov/measles/data-research/index.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Measles Vaccination, Measles (Rubeola) (2025). https://www.cdc.gov/measles/vaccines/index.html.

- Smithsonian, Measles, Mumps, and Rubella Vaccines. https://www.si.edu/spotlight/antibody-initiative/mmr.

- F. Zhou, T. C. Jatlaoui, A. J. Leidner, R. J. Carter, X. Dong, J. M. Santoli, S. Stokley, D. C. Daskalakis, G. Peacock, Health and Economic Benefits of Routine Childhood Immunizations in the Era of the Vaccines for Children Program — United States, 1994–2023. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 73, 682–685 (2024).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, About the National Immunization Surveys (NIS), National Immunization Surveys (2025). https://www.cdc.gov/nis/about/index.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Vaccination Coverage and Exemptions among Kindergartners, SchoolVaxView (2024). https://www.cdc.gov/schoolvaxview/data/index.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Routine Measles, Mumps, and Rubella Vaccination, Vaccines & Immunizations (2021). https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/mmr/hcp/recommendations.html.

- HRSA Health Resources & Services Administration, Defining Rural Population (2024). https://www.hrsa.gov/rural-health/about-us/what-is-rural.

- J. M. Santoli, M. C. Lindley, M. B. DeSilva, E. O. Kharbanda, M. F. Daley, L. Galloway, J. Gee, M. Glover, B. Herring, Y. Kang, P. Lucas, C. Noblit, J. Tropper, T. Vogt, E. Weintraub, Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Routine Pediatric Vaccine Ordering and Administration — United States, 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 69, 591–593 (2020).

- C. A. Bramer, L. M. Kimmins, R. Swanson, J. Kuo, P. Vranesich, L. A. Jacques-Carroll, A. K. Shen, Decline in Child Vaccination Coverage During the COVID-19 Pandemic — Michigan Care Improvement Registry, May 2016–May 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 69, 630–631 (2020).

- J. R. Zucker, J. B. Rosen, M. Iwamoto, R. J. Arciuolo, M. Langdon-Embry, N. M. Vora, J. L. Rakeman, B. M. Isaac, A. Jean, M. Asfaw, S. C. Hawkins, T. G. Merrill, M. O. Kennelly, B. Maldin Morgenthau, D. C. Daskalakis, O. Barbot, Consequences of Undervaccination — Measles Outbreak, New York City, 2018–2019. N Engl J Med 382, 1009–1017 (2020).

- World Health Organization, Worldwide measles deaths climb 50% from 2016 to 2019 claiming over 207 500 lives in 2019 (2025). https://www.who.int/news/item/12-11-2020-worldwide-measles-deaths-climb-50-from-2016-to-2019-claiming-over-207-500-lives-in-2019.

- H. A. Hill, L. D. Elam-Evans, D. Yankey, J. A. Singleton, Y. Kang, Vaccination Coverage Among Children Aged 19–35 Months — United States, 2017. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 67, 1123–1128 (2018).

- A. N. Albers, J. Thaker, S. R. Newcomer, Barriers to and facilitators of early childhood immunization in rural areas of the United States: A systematic review of the literature. Prev Med Rep 27, 101804 (2022).