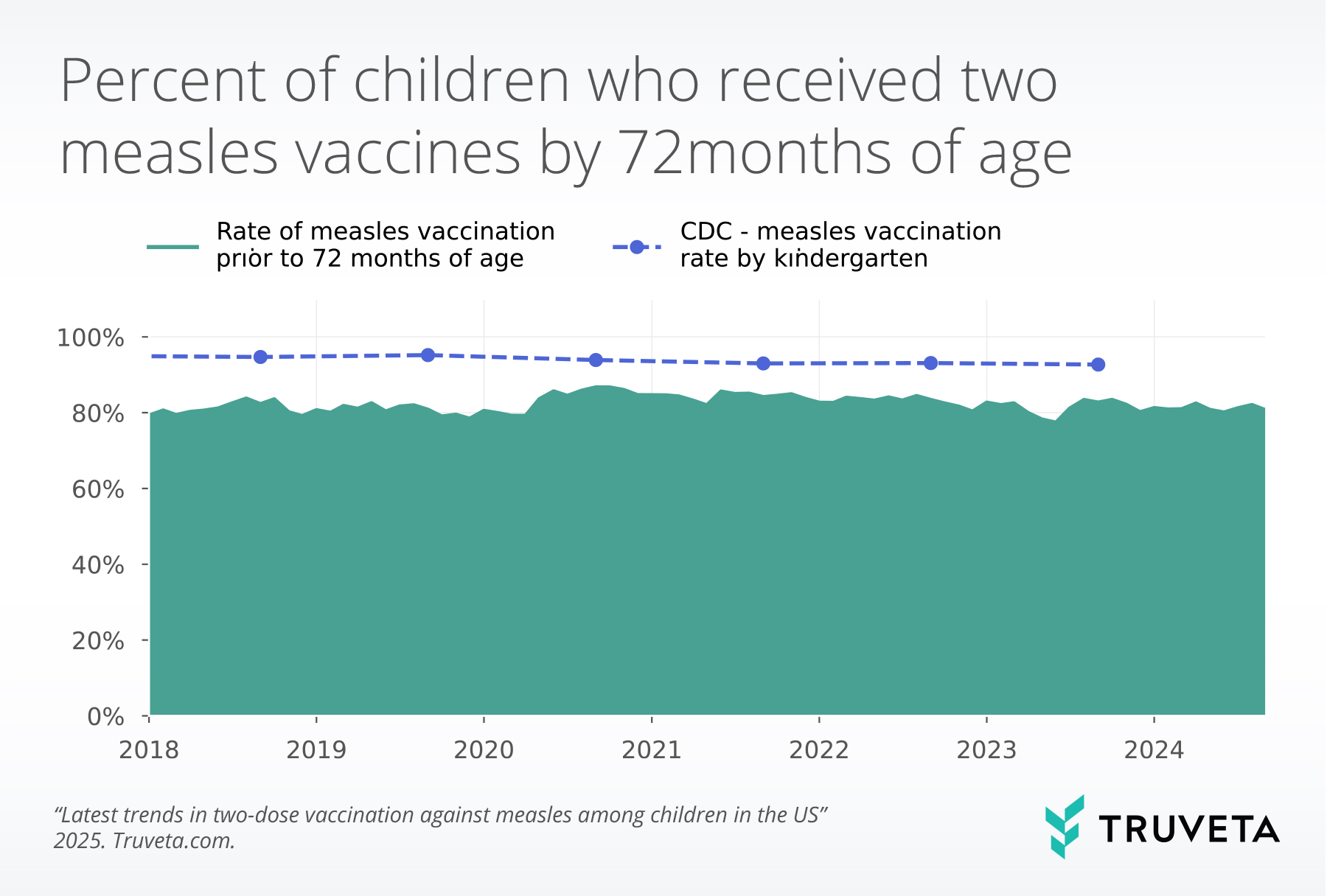

- The vaccination rate by age six fluctuated between 2018 and 2021; however, rates have decreased since 2021. The rate in 2021 was 81.9% compared to 80.4% in 2024. This means for every 70 children, roughly one more child received two measles vaccines in 2021 compared to 2024.

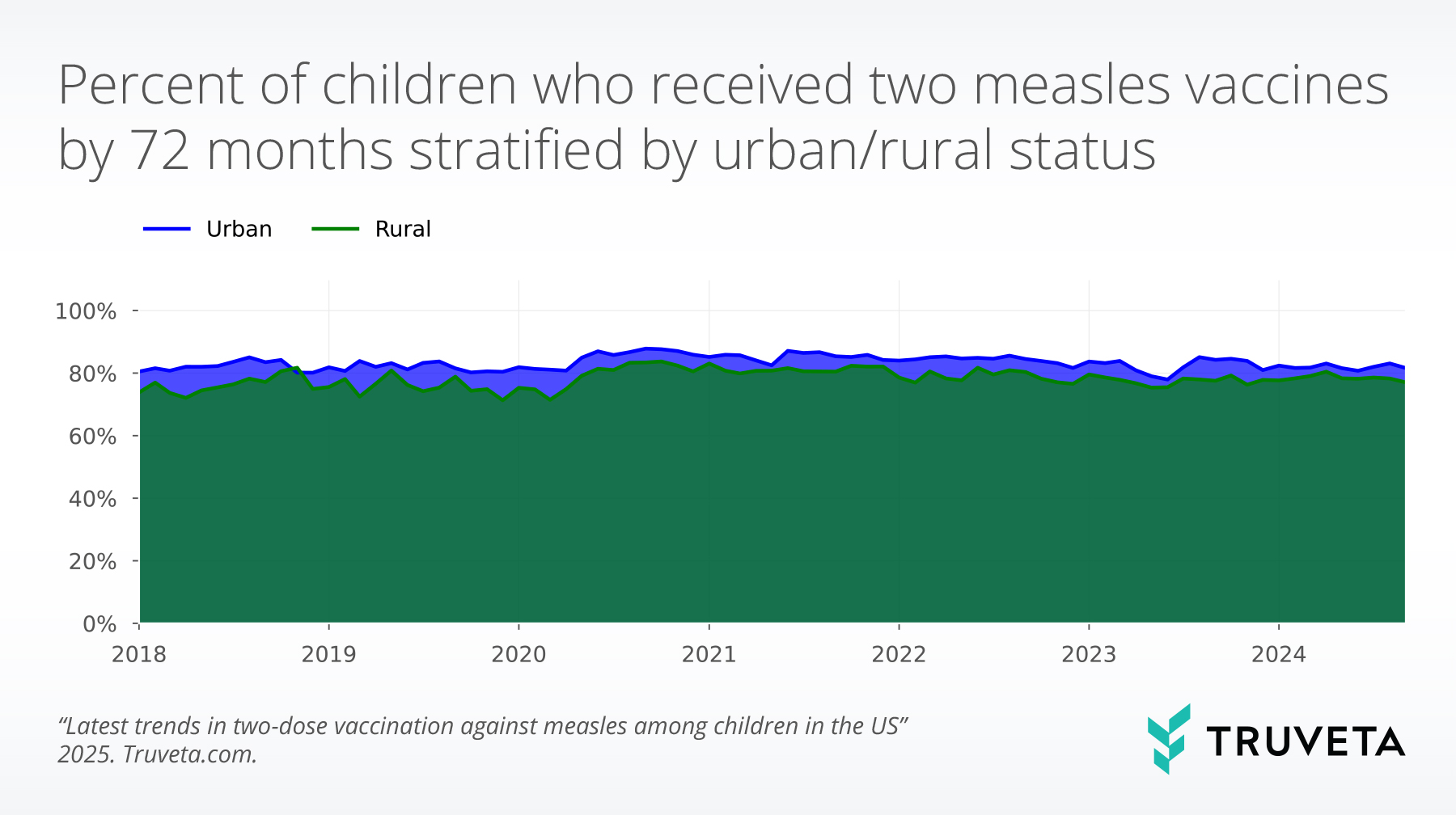

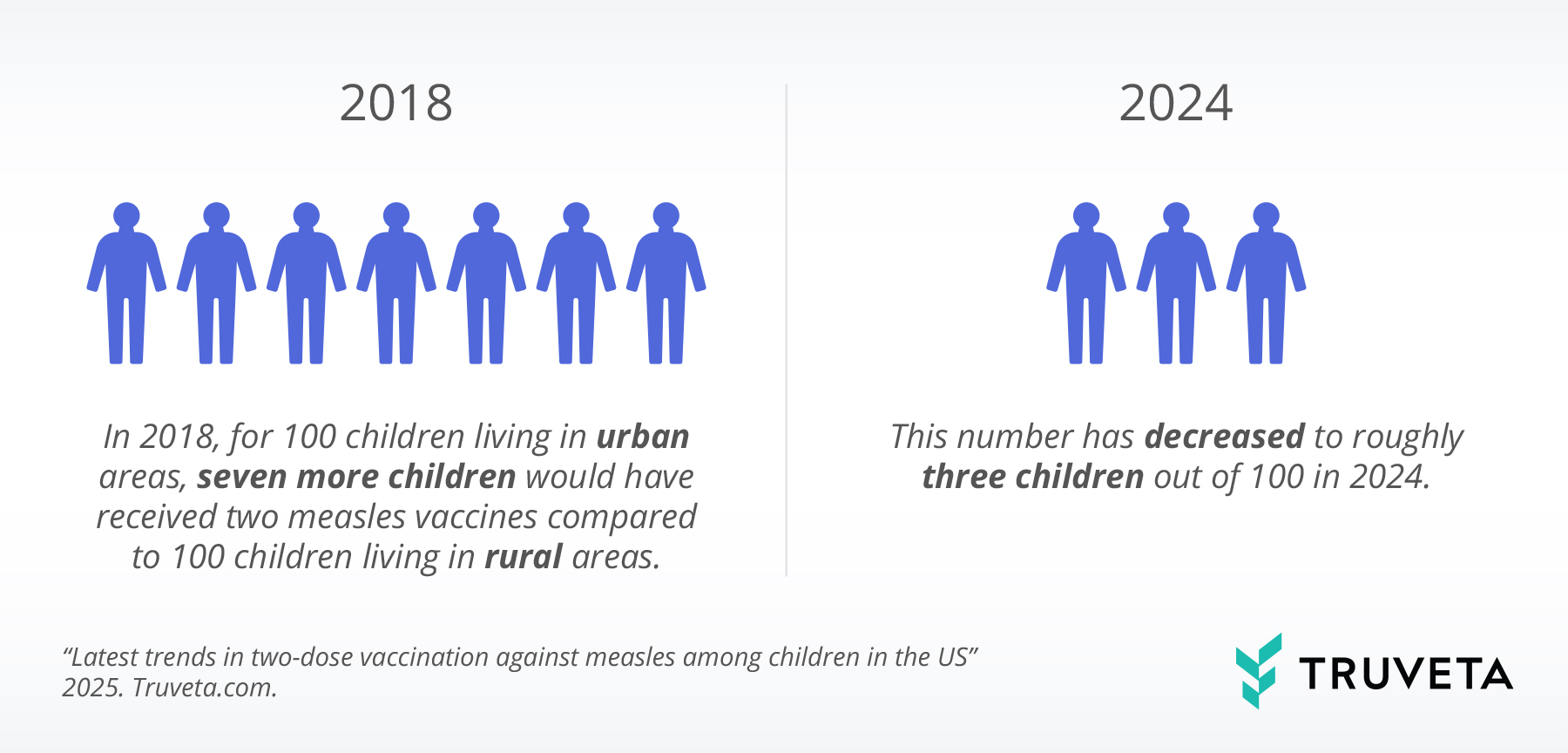

- The percentage of children with two measles vaccines by age six was higher for children living in urban areas compared to rural areas for all years studied; however, the difference in rates has decreased. In 2018, for 100 children living in urban areas, seven more children would have received two measles vaccines compared to 100 children living in rural areas. This number has decreased to roughly three children out of 100 in 2024.

Measles remains one of the most contagious human diseases, with severe complications including pneumonia, encephalitis, hospitalization, and death (1, 2). The introduction of the first measles vaccine in 1963 led to a significant decline in cases (3, 4), and a single dose of the measles vaccine (administered in the US as measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) or measles-mumps-rubella-varicella (MMRV)) is highly effective (93%). In 1989, the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) formally recommended a routine two-dose measles vaccination schedule: the first dose administered at 12 to 15 months, and the second dose at 4 to 6 years of age (5). A second dose further improves protection, with the two-dose series 97% effective against measles (6).

Following widespread adoption, measles cases in the US dropped dramatically, leading to the disease’s elimination from the US in 2000 (3). This second dose has played a critical role in maintaining high population-level immunity and preventing outbreaks, especially as measles cases continue to rise globally (7).

We’ve shared trends of first-time vaccination rates for children by 23 months of age. In this follow-on analysis, we examine month-level second-dose measles (MMR or MMRV) vaccination rates. We describe the historical trends and compare to the CDC-reported rates of immunization coverage at kindergarten entry (8). Understanding timely measles vaccination patterns is crucial as we see increased measles transmission across Texas and much of the United States in 2025 (9). Maintaining high measles vaccination coverage is essential to slow transmission amid current outbreaks and prevent future ones.

Methods

Using a subset of Truveta Data, we included a population of children who had an outpatient encounter prior to the age of one year, between 12 to 15 months, and between 48 to 72 months. We required the visit between 48 to 72 months to be between January 2018 and September 2024. The time period allowed children to have sufficient time to reach 72 months of age.

We identified children who received a measles vaccine (MMR or MMRV) and the age at which they received the vaccine. Vaccination events recorded prior to age 6 months (182 days) were assumed to be erroneous and excluded (10). Vaccines were required to be at least 28 days apart (6).

Fully vaccinated by 72 months (age six)

We identified children who received a second vaccine prior to 72 months of age (age six). For this analysis, measles vaccine doses received from 6 to 11 months were ignored, and two additional vaccines were required to be considered fully vaccinated. This is in alignment with the CDC guidelines, as this early dose is considered a zero dose, not a replacement for the 12 to 15 month dose (6).

We plot the unadjusted monthly rates of second measles dose administered per children with an outpatient encounter from 48 to 72 months. Children were only counted in one month. If they had multiple encounters between 48 to 72 months, the last was selected. All children who received the vaccine were plotted in the month of their 48 to 72 month visit, regardless of when they received the vaccine. The monthly rates are plotted from January 2018 to September 2024. We also plot data from CDC’s School Vax View data, which presents an annual rate of children who received two doses of a measles vaccine amongst kindergarteners in the US (the latest represents children during the 2023-2024 school year). The CDC data were shifted to September of the first calendar year (i.e., for the 2023/2024 school year, the data are plotted in September 2023).

Rates stratified by urban/rural residency

We stratified the data by rural versus urban residency using the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy Data Files (11). A threshold of 0.3 was used in this study to differentiate between rural and urban status. We calculated the unadjusted rate of children who received a vaccination by 72 months of age. We plot and describe the differences in vaccination status by residency.

Time between vaccine doses

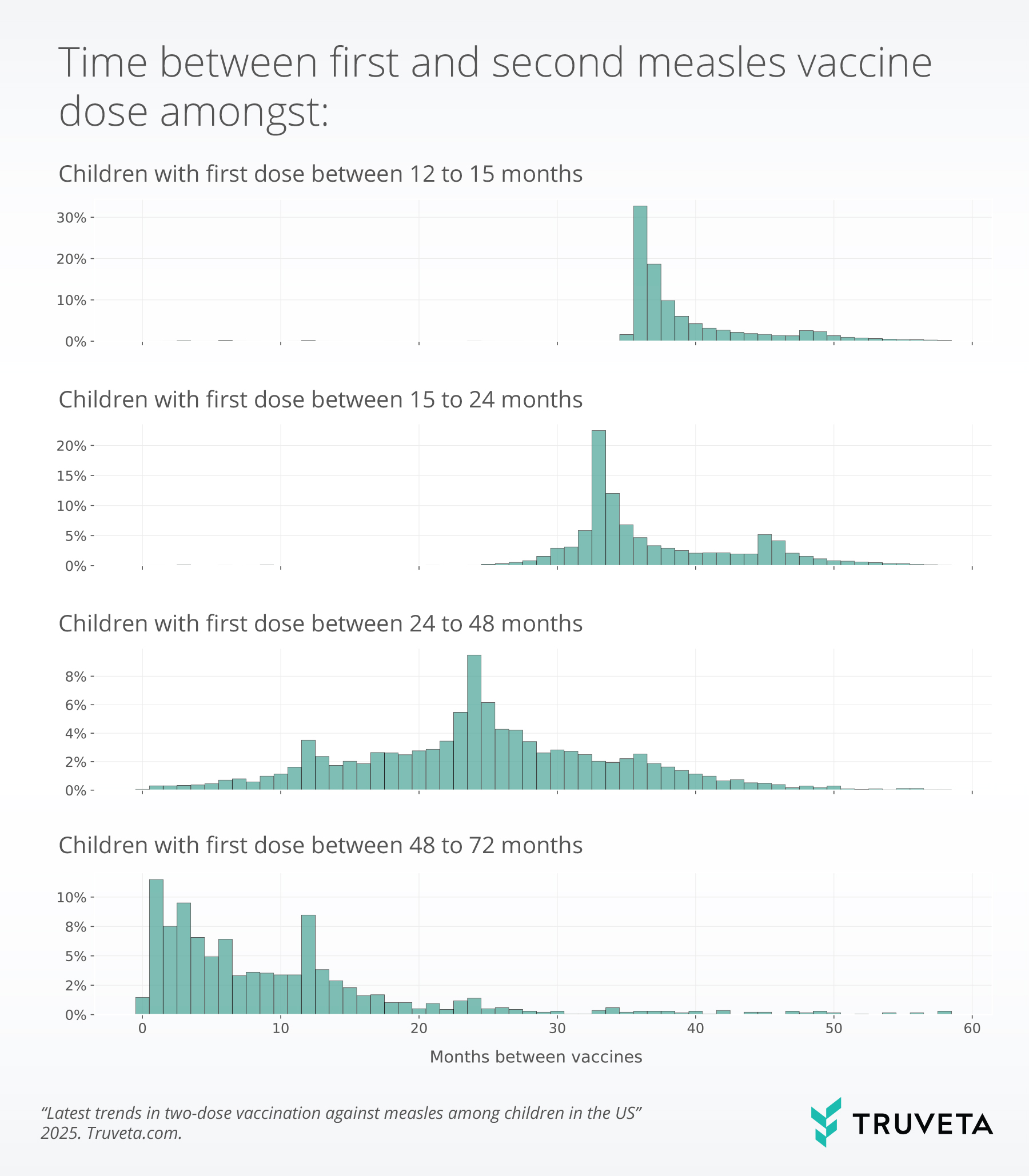

Finally, we plot and describe the time in months between first and second measles dose based on the age at first vaccination.

You can view this study — including definitions and code — directly in Truveta Studio.

Results

We included 379,590 children in this analysis. Of the children in this study, 93.9% had at least one measles vaccine during the study period and 83.0% received two doses.

Fully vaccinated by 72 months (age six)

The vaccination rate by 72 months fluctuated between 2018 and 2021; however, rates have decreased since 2021. The rate in 2021 was 81.9% compared to 80.4% in 2024.

This means for every 70 children, roughly one more child received two measles vaccines in 2021 compared to 2024.

On average, the rates we present are 13.5 percentage points lower than the rates reported by the CDC in the School Vax View.

Rates stratified by urban/rural residency

The percentage of children with two measles vaccines by 72 months was higher for children living in urban areas compared to rural areas for all years studied; however, the difference in rates has decreased.

In 2018, for 100 children living in urban areas, seven more children would have received two measles vaccines compared to 100 children living in rural areas. This number has decreased to roughly three children out of 100 in 2024.

Time between vaccine doses

Among children who received two measles vaccine doses by 72 months, a small percentage of the overall population received their first vaccine after 24 months; 1.5% of the population received their first dose between 24 and 47 months, and 0.4% of the population received their first vaccine between 48 and 72 months.

We observe variation in time between vaccines based on age at first measles vaccine. For children who received their first vaccine between 12 and 24 months, nearly all received their second vaccine more than a year after the first.

For children who received their first vaccine between 24 to 48 months, 8.3% received their second vaccine more than a year later, while 64.1% of children who received their first vaccine after 48 months received the second vaccine within one year.

Discussion

Overall, we found the completion rates for the second dose of the measles vaccine by 72 months of age are lower than those reported by the CDC at kindergarten entry. There are a number of reasons for this discrepancy. First, the underlying populations studied may be different between the two analyses (i.e., children with outpatient visits in Truveta Data versus sampled children attending kindergarten). Second, school vaccination coverage estimates may be overestimated due to inaccurate documentation, such as if parents report vaccine history verbally without providing written documentation. Additionally, many states sample kindergarteners to provide vaccination coverage estimates to CDC, rather than providing a true population estimate. These methods may introduce sampling bias if the sampled population is not truly representative (8). Finally, homeschooling rates have increased dramatically since the COVID-19 pandemic, with the 2022-2023 school year seeing a 51% increase in homeschooled children compared to the 2017-2018 school year (12), accounting for an estimated 3 million homeschooled children in the 2022 school year (13). Homeschooled children would not be captured in the CDC data, and likely would have lower vaccination rates, a potential contributing factor to the lower measles coverage rates observed in our study.

Our analysis suggests that while disparities were pronounced by urban or rural status in receipt of the first dose of the measles vaccine, these disparities are substantially reduced by the time of the second measles vaccine, which children receive prior to kindergarten entry, especially in recent years. Barriers to vaccination in rural settings include longer distance to clinics, challenges with transportation, and shortages of primary care providers (14). The longer window available to receive the second dose of measles vaccine (2 years, from age 4-6 years) may allow for some of these barriers to be overcome, as compared with a 3-month window for timely completion of the first dose (12-15 months). This result is encouraging, highlighting that regardless of urbanicity, parents are vaccinating their children prior to kindergarten entry, as is required in all 50 states (15).

In this analysis, we also observed a higher percentage of children receiving the second vaccine within one year of their first dose if they received their first dose after 48 months, compared to children who received the vaccine prior to 48 months. This suggests children in this age group may be catching up on vaccines prior to starting kindergarten, again supporting that susceptibility in younger children may be somewhat corrected by kindergarten entry to meet school requirements. While encouraging that children are receiving vaccines to meet school entry requirements, measles is most severe for young children, and addressing vaccine hesitancy and delay among those at greatest risk for complications is an important public health challenge (16).

There are a few limitations with this study. First, the analysis is based on unadjusted rates and does not account for demographic or socioeconomic factors that may influence vaccination uptake. Second, measles vaccination records rely on electronic health data, which may be incomplete if a child’s vaccination occurred outside of a Truveta member healthcare system. Additionally, the data presented here are based upon children who have at least four years of data within a Truveta constituent health system (an outpatient encounter in the first year of life and between the ages of 48 to 72 months). These inclusion criteria were enforced to ensure we were capturing full vaccination requirements; however, this sample does not include populations who moved during this period or who did not have regular interactions with the healthcare system.

These are preliminary research findings and not peer reviewed. Data are constantly changing and updating. These findings are consistent with data accessed on March 28, 2025.

Citations

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, About Measles, Measles (Rubeola) (2024). https://www.cdc.gov/measles/about/index.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Measles Symptoms and Complications, Measles (Rubeola) (2024). https://www.cdc.gov/measles/signs-symptoms/index.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, History of Measles, Measles (Rubeola) (2024). https://www.cdc.gov/measles/about/history.html.

- Smithsonian, Measles, Mumps, and Rubella Vaccines. https://www.si.edu/spotlight/antibody-initiative/mmr.

- M. Prevention, Recommendations of the Immunization Practices Advisory Committee (ACIP). MMWR 38, 1–18 (1989).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Measles Vaccination, Measles (Rubeola) (2025). https://www.cdc.gov/measles/vaccines/index.html.

- World Health Organization, Measles cases surge worldwide, infecting 10.3 million people in 2023 (2024). https://www.who.int/news/item/14-11-2024-measles-cases-surge-worldwide–infecting-10.3-million-people-in-2023.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Vaccination Coverage and Exemptions among Kindergartners, SchoolVaxView (2024). https://www.cdc.gov/schoolvaxview/data/index.html.

- Texas Health and Human Services, Measles Outbreak – March 28, 2025 (2025). https://www.dshs.texas.gov/news-alerts/measles-outbreak-2025.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Routine Measles, Mumps, and Rubella Vaccination, Vaccines & Immunizations (2021). https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/mmr/hcp/recommendations.html.

- HRSA Health Resources & Services Administration, Defining Rural Population (2024). https://www.hrsa.gov/rural-health/about-us/what-is-rural.

- P. Jamison, L. Meckler, P. Gordy, C. E. Morse, C. Alcantara, Home schooling’s rise from fringe to fastest-growing form of education (2024). https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/interactive/2023/homeschooling-growth-data-by-district/.

- National Home Education Research Institute, Homeschooling: The Research (2025). https://nheri.org/research-facts-on-homeschooling/.

- A. N. Albers, J. Thaker, S. R. Newcomer, Barriers to and facilitators of early childhood immunization in rural areas of the United States: A systematic review of the literature. Prev Med Rep 27, 101804 (2022).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “State School Immunization Requirements and Vaccine Exemption Laws” (2022); https://www.cdc.gov/phlp/docs/school-vaccinations.pdf.

- J. Gold, More parents are delaying their kids’ vaccines, and it’s alarming pediatricians (2024). https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2024-03-11/parents-delaying-kids-vaccines-posing-risk-to-toddlers.