The United States has some of the highest rates of adverse maternal health outcomes compared to other high-income countries (Creanga et al., 2015; Gunja et al., 2022; Taylor et al., 2022). These outcomes have only increased in the last decade (Hoyert, 2023; U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2022). Black women continue to experience much worse outcomes during pregnancy and delivery compared to white women. Even more devasting, Black women experience maternal mortality at 3x the rate of white women (Runkle et al., 2022; Shen et al., 2022; Taylor et al., 2022).

Preeclampsia is a complication that can occur during pregnancy and affects approximately 8 to 10% of pregnancies in the US (Ford et al., 2022; Wheeler et al., 2022). Preeclampsia is characterized by high blood pressure and occurs most often during a person’s first pregnancy (National Institutes of Health, 2022; U.S. Preventive Services, 2023). Left untreated, preeclampsia can cause maternal seizure (eclampsia), stroke, hemorrhage, kidney and cardiac injury. Eclampsia may have contributed to the Olympian Tori Bowie’s death in June of this year (Chappell, 2023).

Recent studies have suggested women with preeclampsia experience higher rates of heart failure following delivery. Heart failure risk factors are often preventable and modifiable, but heart failure is not typically considered a potential health problem for healthy women of childbearing age.

Dr. Emily Garrett, co-author on our recent pre-print and practicing obstetrician and gynecologist at Providence stated, “We are in the midst of a maternal health crisis in the United States. One of the leading causes of maternal morbidity and mortality is hypertensive disease during and shortly after delivery. Prioritization of research is essential. The more we understand about the disease, the more awareness it creates among fellow physicians, patients, and policy makers.”

The purpose of this study is to determine whether having a diagnosis of preeclampsia at or before delivery increases the rate of heart failure after delivery across age, race, and ethnicity demographic characteristics and obstetrics related comorbidities.

Methods

We looked at a subset of the Truveta Data and identified females aged 16-50 years of age who had deliveries between January 1, 2018, and March 31, 2023. Using the first delivery within the timeframe we identified patients with pre-eclampsia.

Patients were excluded if they did not have information on sex, race, ethnicity, age, if their last contact with the health care system was on the date of delivery, or if they had recent history of congenital heart disease, heart disease, chronic kidney disease, pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction, cardiomyopathy, or ischemic heart disease less than a year prior to delivery.

We identified patients who had heart failure on or after delivery and used Cox proportional hazards to assess time till heart failure. More details of the methods can be found in our preprint: The temporal relationship between preeclampsia and heart failure | medRxiv.

Results

In this retrospective cohort study that included over 700,000 patients with deliveries. 2% of patients received a diagnosis of preeclampsia at or before delivery and of those, 69 experienced heart failure events after delivery.

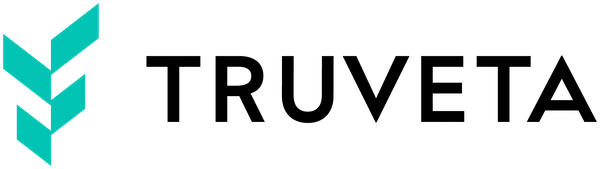

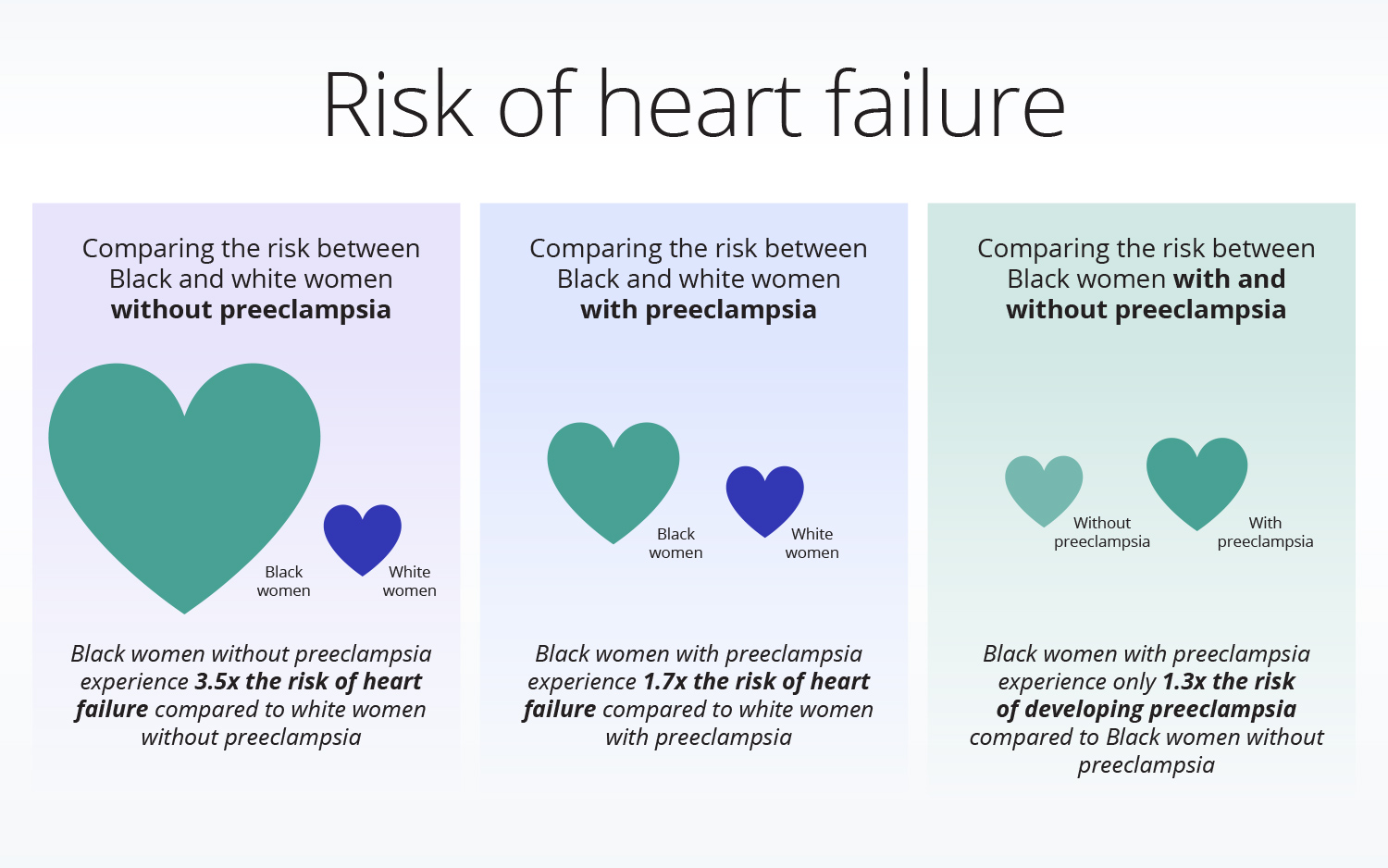

The risk of heart failure at any point after delivery was 2.82 times greater in women that had preeclampsia than those that did not, after controlling for obstetric comorbidities, race, ethnicity, and age. After adjusting for obstetric comorbidities, race, ethnicity, age and disability, Black patients had a higher risk of heart failure compared to white women (HR 3.48; CI 2.97, 4.06). Black patients with preeclampsia had a higher risk of heart failure than white patients without preeclampsia (HR 4.63; CI 1.65, 12.99). Black patients without preeclampsia had a risk of heart failure similar to other racial groups with preeclampsia.

In these images, we get some information about where we want to focus our energy for prevention. The risk of heart failure is greater for Black women without preeclampsia (compared to white women without preeclampsia), for Black women with preeclampsia (compared to white women with and without preeclampsia), and for white women with preeclampsia (compared to white women without preeclampsia). Interestingly, the risk of heart failure for Black women with preeclampsia is about the same as Black women without preeclampsia.

The variables that we identified as the most important for the occurrence of heart failure are non-modifiable socio-demographic factors (e.g., race, ethnicity) and preventable or modifiable disease (e.g., BMI ≥40, pre-gestational diabetes).

Discussion

In this study, we found patients with preeclampsia are at high risk for heart failure both within 90 days and overall. Regular, long-term clinical follow up or screening of women with preeclampsia for heart failure may be warranted.

Even following resolution, preeclampsia is a significant risk factor for future cardiovascular disease, but there is no regular implementation of long-term clinical follow up or screening in the US. Regular long-term clinical follow up or screening for heart failure may be warranted for women with preeclampsia.

Maternal health care providers play a critical role ensuring the well-being of expectant mothers. Typically, six weeks after delivery, the ongoing care of the new mother shifts from an OBGYN to a primary care provider (PCP). The PCP’s role of continued care includes reviewing the patient’s medical history, assessing the patient for risk factors (including screening for heart failure), monitoring symptoms, screening for relevant diseases, completing regular check-ups with the patient, and managing medications and referrals as needed. Dr. Garrett shared, “Preeclampsia has been around for centuries, yet we have a rudimentary understanding of its causes, few effective tools to prevent and treat it, and a poor understanding regarding its long-term effects. With this ongoing research we will better understand the long-term consequences of the disease. The hope is to be better able to partner with patients as they move beyond pregnancy and to screen for and prevent future morbidity and mortality.”

There is an urgent need across different provider types for a collective effort to address one of the most significant threats to maternal health – preeclampsia. Although there are many factors that may make an impact this in this area, we call on two:

- Increased patient understanding through listening: A crucial aspect of delivering excellent patient care lies in a provider’s ability to listen attentively to their patients. By valuing and embracing the power of active listening, patient outcomes can be improved, stronger provider-patient relationships can be built, and a healthcare environment that prioritizes empathy and understanding can be fostered.

- Clear communication: Medical expertise is only as good as a provider’s ability to make prompt diagnoses and carry out treatment plans. This requires careful explanation to patients regarding symptoms of concern and explanations of when seeking immediate care is recommended. It also requires providers to communicate effectively amongst other medical professionals. This not only means appropriate and accessible documentation within EHRs, but also effective communication and education about obstetric diagnoses like preeclampsia. Other specialties — like emergency, internal medicine, and cardiology — may be less familiar with maternal health outcomes, but who will undoubtedly see these patients at times of high need and be integral to their care beyond the pregnancy and postpartum period.

Together, let’s continue to push for a transformative movement that aims to revolutionize the way patients are diagnosed with preeclampsia and managed to prevent additional adverse outcomes (such as heart failure), ultimately empowering mothers and saving lives.

Check out the preprint to learn more about this study, the methods, and data included in the analysis described here.

These are preliminary research findings and not peer reviewed. Data are constantly changing and updating. These findings are consistent with data accessed on July 25, 2023.

Citations

Chappell, B. (2023, June 13). Tori Bowie, an elite Olympic athlete, died of complications from childbirth. https://www.npr.org/2023/06/13/1181971448/tori-bowie-an-elite-olympic-athlete-died-of-complications-from-childbirth

Creanga, A. A., Berg, C. J., Syverson, C., Seed, K., Bruce, F. C., & Callaghan, W. M. (2015). Pregnancy-Related Mortality in the United States, 2006–2010. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 125(1), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000000564

Ford, N. D., Cox, S., Ko, J. Y., Ouyang, L., Romero, L., Colarusso, T., Ferre, C. D., Kroelinger, C. D., Hayes, D. K., & Barfield, W. D. (2022). Hypertensive Disorders in Pregnancy and Mortality at Delivery Hospitalization—United States, 2017–2019. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 71(17), 585–591. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7117a1

Gunja, M. Z., Gumas, E. D., & Williams II, R. D. (2022). The U.S. Maternal Mortality Crisis Continues to Worsen: An International Comparison. https://doi.org/10.26099/8VEM-FC65

Hoyert, D. L. (2023). Maternal mortality rates in the United States, 2021. Technical report, National 269 Center for Health Statistics (U.S.), March 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/maternal-mortality/2021/maternal-mortality-rates-2021.htm

National Institutes of Health. (2022, June 14). Who is at risk of preeclampsia? https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/preeclampsia/conditioninfo/risk

Runkle, J. D., Matthews, J. L., Sparks, L., McNicholas, L., & Sugg, M. M. (2022). Racial and ethnic disparities in pregnancy complications and the protective role of greenspace: A retrospective birth cohort study. Science of The Total Environment, 808, 152145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152145

Shen, J. J., Mojtahedi, Z., Vanderlaan, J., & Rathi, S. (2022). Disparities in Adverse Maternal Outcomes Among Five Race and Ethnicity Groups. Journal of Women’s Health, jwh.2021.0495. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2021.0495

Taylor, J., Bernstein, A., Waldrop, T., & Smith-Ramakrishnan, V. (2022, March 2). The Worsening U.S. Maternal Health Crisis in Three Graphs. https://tcf.org/content/commentary/worsening-u-s-maternal-health-crisis-three-graphs/

U.S. Government Accountability Office. (2022). Maternal Health: Outcomes Worsened and Disparities Persisted During the Pandemic (GAO-23-105871).

U.S. Preventive Services. (2023). Task Force Issues Draft Recommendation Statement on Screening for Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/sites/default/files/file/supporting_documents/hypertensive-disorders-pregnancy-bulletin.pdf.

Wheeler, S. M., Myers, S. O., Swamy, G. K., & Myers, E. R. (2022). Estimated Prevalence of Risk Factors for Preeclampsia Among Individuals Giving Birth in the US in 2019. JAMA Network Open, 5(1), e2142343. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.42343