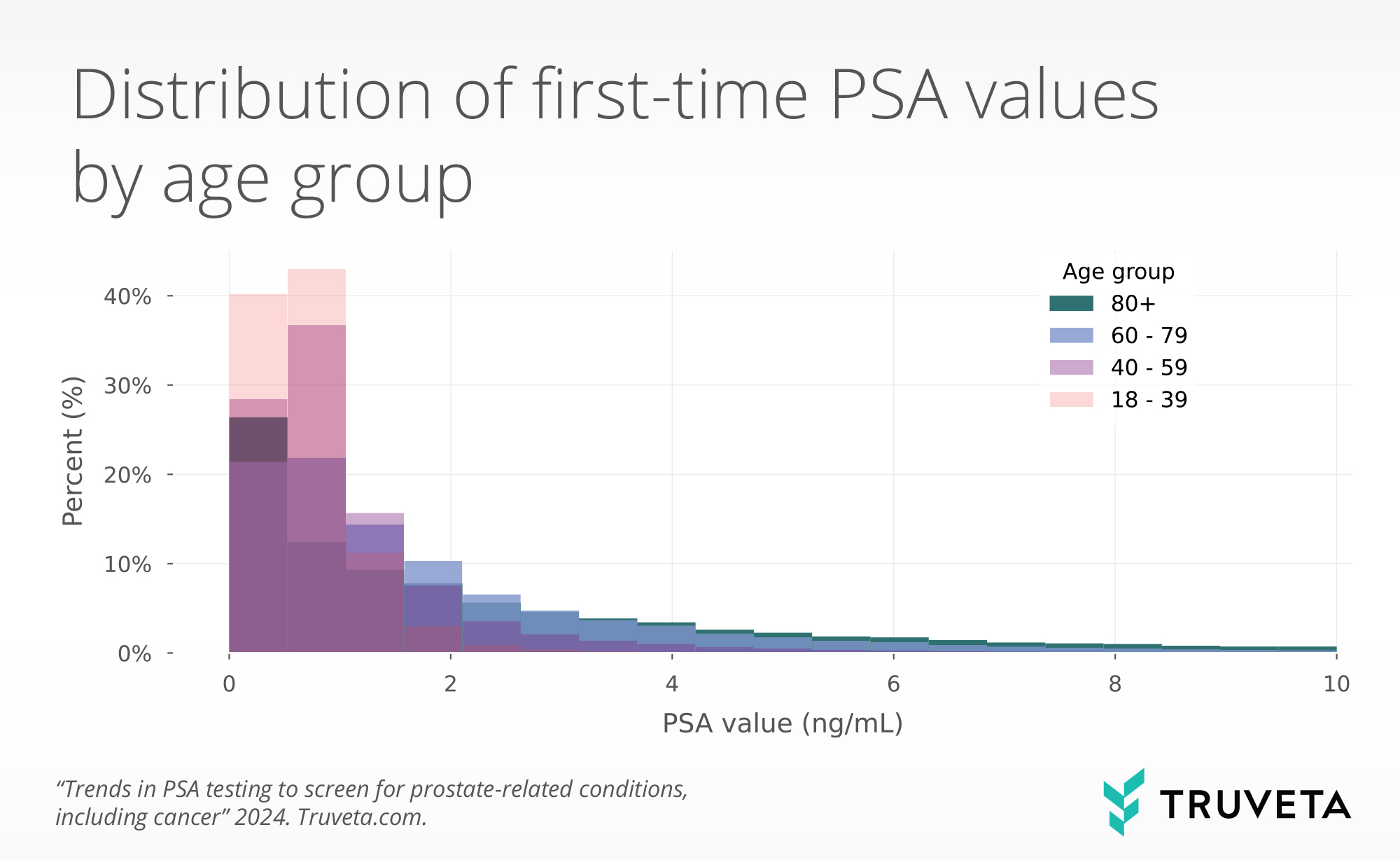

- There are mixed prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening recommendations for men of varying ages. The objective of this study was to describe variation in first-time PSA values across demographic and SDOH factors.

- In a study of nearly 4 million men with PSA lab values, we found higher first-time PSA values for older men, as expected.

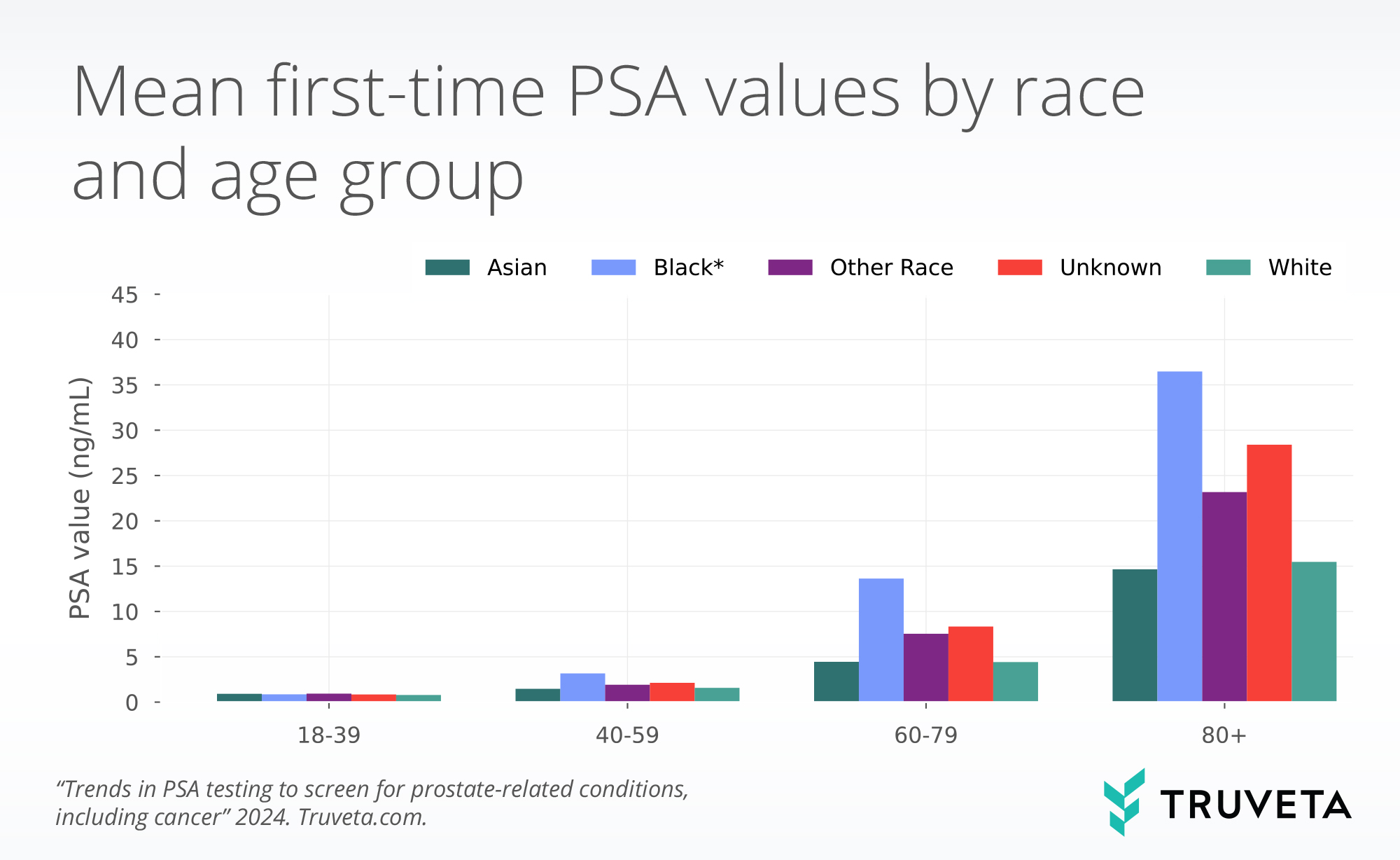

- We also found the mean first-time PSA value was 2.0x, 3.1x, and 2.4x higher for Black patients than white or Asian patients in the 40-59, 60-79, and 80+ year-old age groups, respectively.

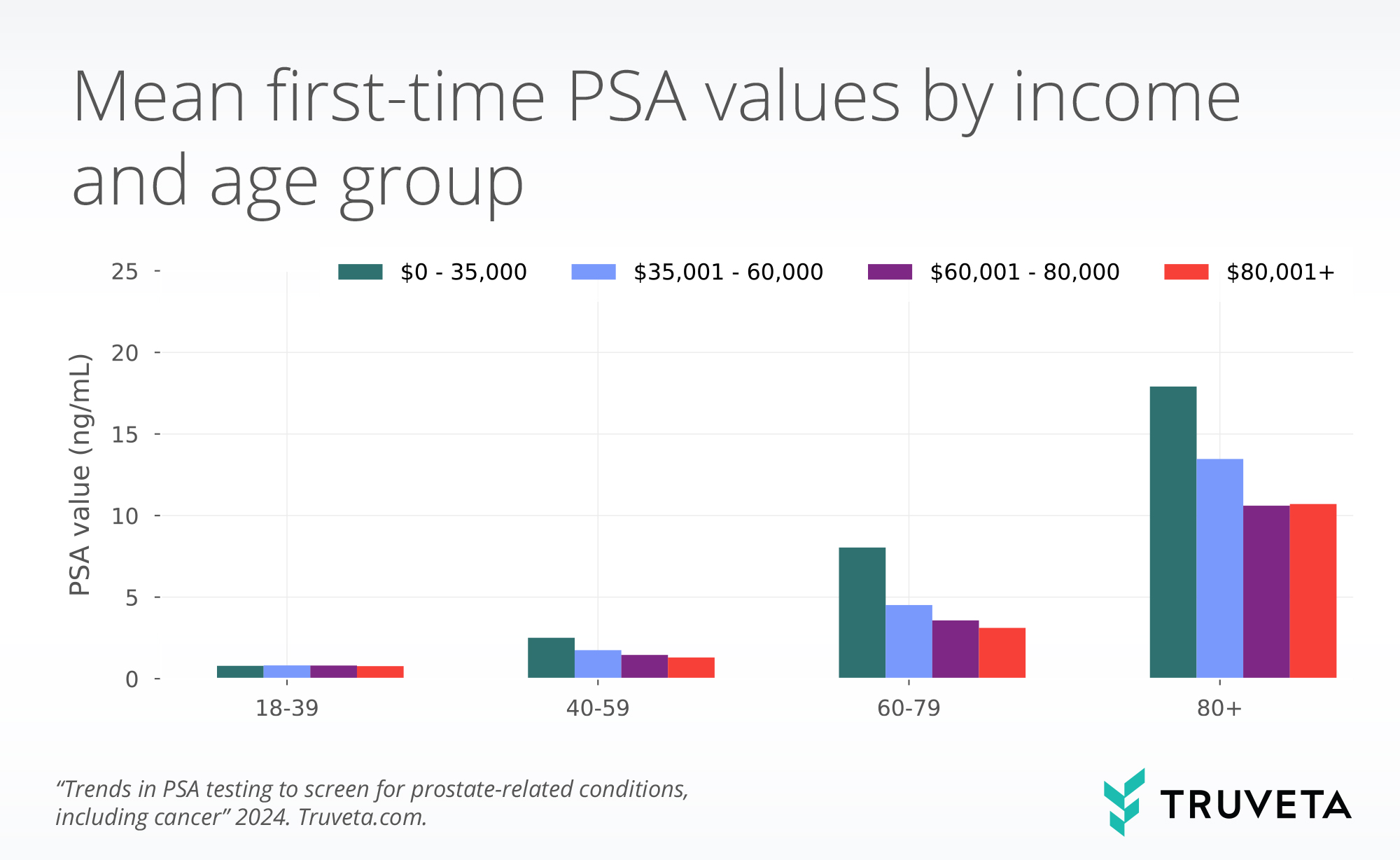

- Men in the lowest income group ($0-35,000) had 1.9x, 2.6x, and 1.7x higher first-time age-specific average PSA values than men in the highest income group ($80,001+) for the 40-59 and 60-79, and 80+ year old age groups.

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) is a protein produced by the prostate gland within males (National Cancer Institute, 2022). It is produced normally; however, prostate cancer, prostatitis, and benign prostatic hyperplasia can cause increased levels. PSA is measured with a blood test and interpreted according to a patient’s age; older patients are expected to have higher non-elevated (normal) PSA values than younger patients (David & Leslie, 2022).

There are mixed screening recommendations for men in certain age groups. While screening can lead to beneficial earlier detection, increased testing can also lead to false positives, causing unnecessary additional screening, tests, and treatment. The US Preventative Servies Task Force recommends that men between the ages of 55–69 should work with a clinical team to determine appropriate screening and the risk/benefit trade off (US Preventive Services Task Force, 2018).

Although the American Urological Association also emphasizes the tradeoffs of risks and benefits (Carter et al., 2013), they provide a strong recommendation that clinicians should offer prostate cancer screening (a PSA test) starting at age 45–50 for men of average risk and men aged 40–45 at high risk, such as people of Black race (Wei et al., 2023). Black non-Hispanic men have the highest age-adjusted rate of new prostate cancer (US Cancer Statistics Working Group and others & others, 2020). Further, Black men are diagnosed with prostate cancer at a younger age compared to their white counterparts and with more severe disease at the time of diagnosis (Pietro et al., 2016; Rawla, 2019). This contributes to the higher than 2x rate of death from prostate cancer for Black men compared to white men (DeSantis et al., 2019).

The objective of this study was to describe the variation in first-time PSA values across demographic and SDOH factors when stratified by age.

To explore the study definitions, population, methods, and more, check out the study in Truveta Studio.

Methods

First-time PSA lab values

PSA lab values over time

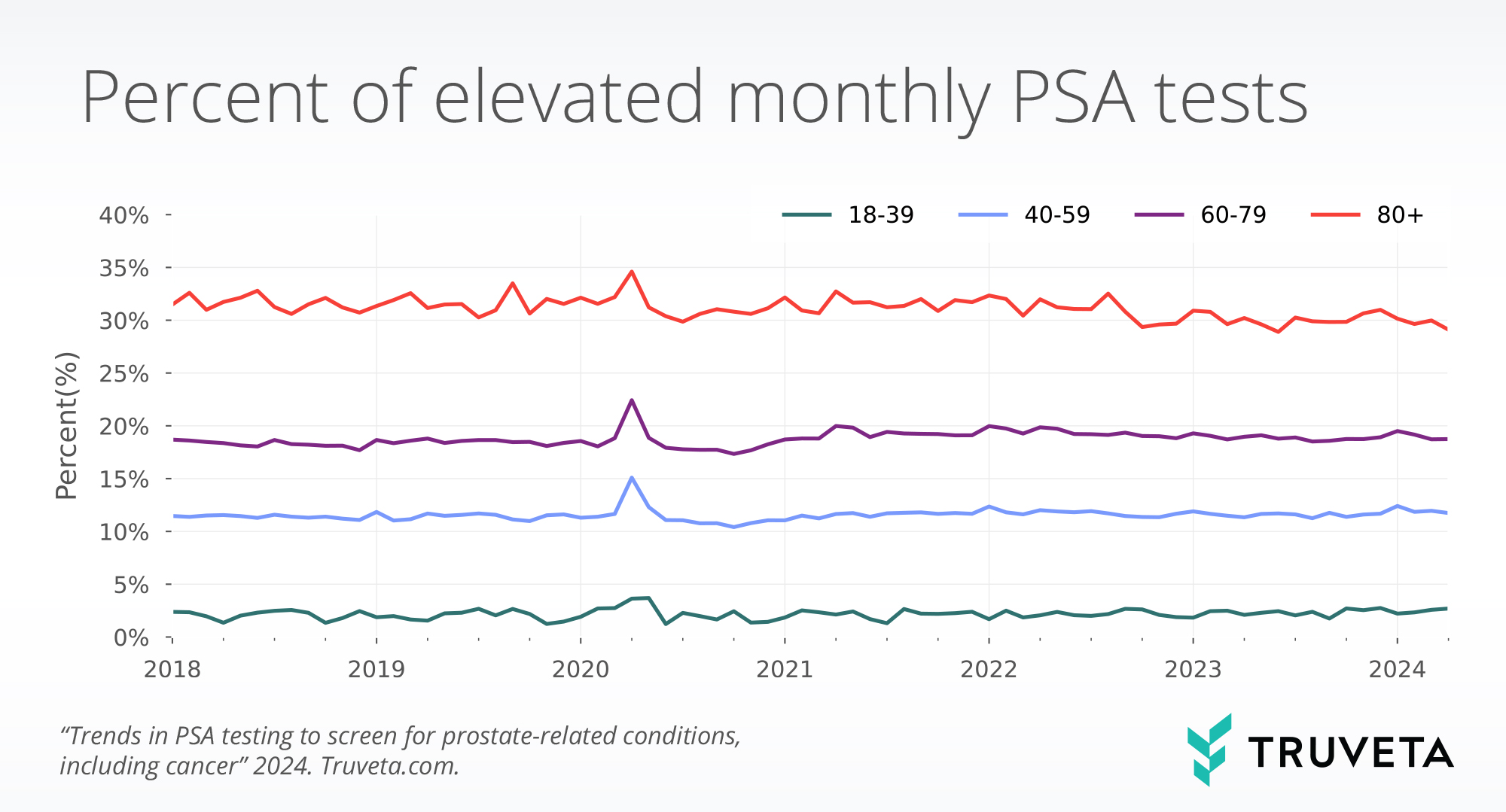

We plotted the percent of elevated lab values over time per all lab values, stratified by age group.

Results

First-time PSA values

PSA values typically occur in a range of 0-10, but extreme high values can occur. This is reflected in high standard deviations observed in this study (Punglia et al., 2006).

PSA lab testing over time

Discussion

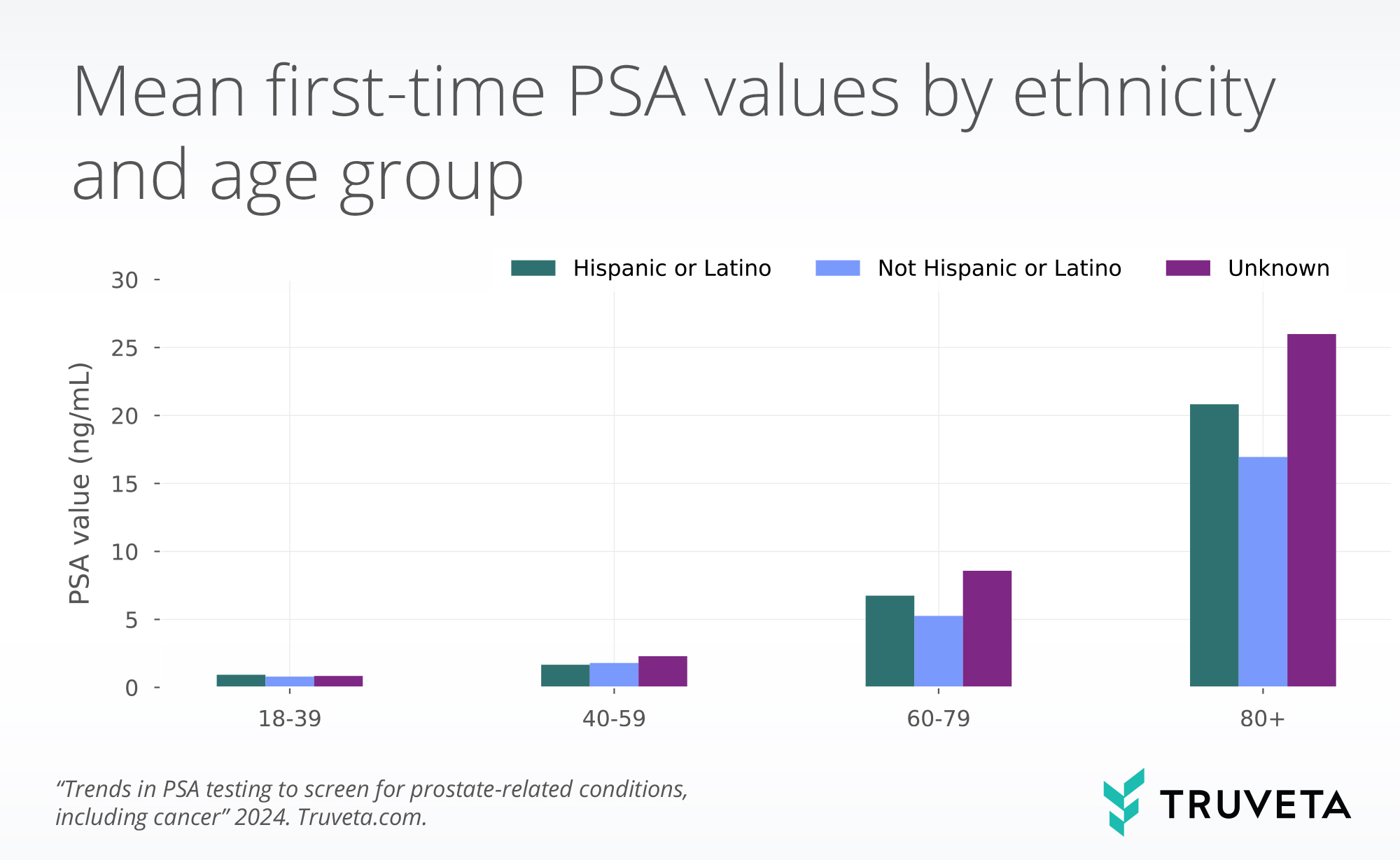

In this study, we described both the rate of PSA testing for men by age group and demographic and SDOH differences in first-time PSA values. Consistent with the literature, we found higher first-time values for men in older age groups and Black men (David & Leslie, 2022; US Cancer Statistics Working Group and others & others, 2020). Interestingly for the three age groups over 40 years of age, we found higher first-time PSA values were associated with lower individual income. Although this may represent additional disparities, caution should be taken when interpreting these results independently as we did not adjust for any other factors. As expected, we saw lognormally distributed PSA values, yielding high standard deviations (Punglia et al., 2006). This is expected as a few extremely elevated values will increase the standard deviations. PSA values are presented on a raw scale in this analysis for interpretability, but log-transformation could be used to handle the non-normality in future analyses

We also saw a small increase in the percentage of monthly PSA tests that were considered elevated. It’s unclear whether this small increase is clinically relevant. Further, it’s important to acknowledge that the interpretation of elevated values is not necessarily indicative of prostate cancer or other prostate-related illnesses. Subsequently, non-elevated values do not confirm that a person does not have prostate cancer or prostate-related illnesses. After a high PSA test, additional testing is considered standard of care (Cleveland Clinic, 2024). We also saw an increased percentage of elevated tests during 2020. This is likely due to a decrease in overall PSA tests being conducted, and therefore tests that were done were of greater medical necessity.

There are a few limitations with this study. First, as previously mentioned, no statistical comparisons between groups were conducted, and we therefore did not control for underlying factors. Second, we did not exclude people with prostate cancer, prostatitis, or other prostate-related illnesses, which may increase their PSA values. Additional and important work can be conducted in this space to understand PSA distributions for populations with specific diseases, such as prostate cancer.

These are preliminary research findings and not peer reviewed. Data are constantly changing and updating. These findings are consistent with data accessed on May 14, 2024. View the full study in Truveta Studio.

Citations

Carter, H. B., Albertsen, P. C., Barry, M. J., Etzioni, R., Freedland, S. J., Greene, K. L., Holmberg, L., Kantoff, P., Konety, B. R., Murad, M. H., & others. (2013). Early detection of prostate cancer: AUA Guideline. The Journal of Urology, 190(2), 419–426.

Cleveland Clinic. (2024, April 21). Elevated PSA (Prostate-Specific Antigen) Level. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/symptoms/15282-elevated-psa-prostate-specific-antigen-level

David, M. K., & Leslie, S. W. (2022). Prostate Specific Antigen. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557495/

DeSantis, C. E., Miller, K. D., Goding Sauer, A., Jemal, A., & Siegel, R. L. (2019). Cancer statistics for african Americans, 2019. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 69(3), 211–233.

Kan, H.-C., Hou, C.-P., Lin, Y.-H., Tsui, K.-H., Chang, P.-L., & Chen, C.-L. (2017). Prognosis of prostate cancer with initial prostate-specific antigen >1,000 ng/mL at diagnosis. OncoTargets and Therapy, Volume 10, 2943–2949. https://doi.org/10.2147/OTT.S134411

Kristal, A. R., Chi, C., Tangen, C. M., Goodman, P. J., Etzioni, R., & Thompson, I. M. (2006). Associations of demographic and lifestyle characteristics with prostate‐specific antigen (PSA) concentration and rate of PSA increase. Cancer, 106(2), 320–328. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.21603

National Cancer Institute. (2022, March 11). Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) Test. https://www.cancer.gov/types/prostate/psa-fact-sheet

Nepal, A., Sharma, P., Bhattarai, S., Mahajan, Z., Sharma, A., Sapkota, A., & Sharma, A. (2023). Extremely Elevated Prostate-Specific Antigen in Acute Prostatitis: A Case Report. Cureus. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.43730

Pietro, G. D., Chornokur, G., Kumar, N. B., Davis, C., & Park, J. Y. (2016). Racial Differences in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Prostate Cancer. International Neurourology Journal, 20(Suppl 2), S112-119. https://doi.org/10.5213/inj.1632722.361

Punglia, R. S., D’Amico, A. V., Catalona, W. J., Roehl, K. A., & Kuntz, K. M. (2006). Impact of age, benign prostatic hyperplasia, and cancer on prostate‐specific antigen level. Cancer, 106(7), 1507–1513. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.21766

Rawla, P. (2019). Epidemiology of Prostate Cancer. World Journal of Oncology, 10(2), 63–89. https://doi.org/10.14740/wjon1191

US Cancer Statistics Working Group and others & others. (2020). US Cancer statistics data visualizations tool, based on 2019 submission data (1999-2017): US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute.

US Preventive Services Task Force. (2018, May 8). Final Recommendation Statement Prostate Cancer: Screening. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/prostate-cancer-screening

Wei, J. T., Barocas, D., Carlsson, S., Coakley, F., Eggener, S., Etzioni, R., Fine, S. W., Han, M., Nissenberg, J., Pinto, P. A., & others. (2023). EARLY DETECTION OF PROSTATE CANCER: AUA/SUO GUIDELINE (2023).